I begin with what my colleagues in economics refer to as counterfactuals. I have taken for my topic today the existence of three seemingly separate U.S. scholarly communities that make the study of culture central. Most people assume that the three—typically referred to as “cultural anthropology,” “Cultural Studies,” and “American Studies” are easily distinguishable and often antagonistic to one another. And most people I know frown, furrow their brows, wince, or even smirk when I playfully but deliberately ask if one of these, the one they may be happiest to identify with, might not actually be a form of one or two of the others. For example, consider your own reaction if I were to suggest that American Studies was a type of cultural anthropology, or that Cultural Studies was a type of American Studies. A sense of difference felt by many students and scholars to be “real” is violated by such statements. In fact, to many people these equations appear as nonsensical as if I were to say that a table is a chair and the chair a painting. Moreover, to many, these equations entail not just what they perceive to be an error of fact but also the subjection of a scholarly field they value in terms of a scholarly field of which they are suspicious (even if they are not well-versed in its past or present).

But these “what ifs” are worth pursuing precisely for the cognitive, emotional, ideological, or epistemic discomfort they cause, and what we might learn from asking them. Consider thinking of cultural anthropology as a form of Cultural Studies and a type of American Studies. To make these claims work we would have to drop the notion that cultural anthropology is the study of “primitive” or “marginalized” people in the world, whether in poor societies on other continents or in one’s own society. And we would probably have to argue that all cultural anthropological studies, whether or not conducted in the U.S. (defined territorially), really are ultimately about the U.S. (directly or indirectly). Although the vast majority of anthropologists I know would reject the equation I have just made (at least at first glance), few would argue against my move to drop the notion that cultural anthropology is the study of “primitive” or “marginalized” people in the world. And many would be intrigued (if not necessarily convinced) by the idea that all U.S. cultural anthropological studies regardless of location might ultimately be about the U.S. This second would entail returning to Paul Ricoeur’s idea about certain things that look like they are about “the Self” being addressed “via the detour of ‘the Other.’” In other words, one could say that no matter what society appears to be the focus of some cultural anthropologist’s work the motivation, the frame of analysis, the research agenda, and even the interpretation always index “values,” approaches, and debates in the U.S. and, hence, can validly be read as “data” about the intellectual, social, cultural, political, and even economic life of the U.S. I am not implying that everyone would agree, nor that everyone must agree, but that these are two potential stumbling blocks that are not insurmountable.

Likewise, I think it is useful to ask, what if we contemplated seeing U.S. American Studies as a type of Cultural Studies (at least a U.S.-style Cultural Studies)? To make this statement work would we not have to drop the notion that American Studies is the study of everything and anything about the U.S., from its health care system to the changing character of the U.S. economy to U.S. foreign policy, unless we were to broaden the understanding of “culture” to such a degree that it encompassed nearly everything (and in so doing became “anthropological”)? And, in acknowledging that “Cultural Studies” itself (with a capital C and a capital S) does not mean the same thing as some broadly construed study of culture and the cultural, would we not also have to drop the notion that all studies of meaning and symbolism, cognition, aesthetics, mastery, and virtuosity belong in “American Studies”?

I opened this essay by saying that I would begin with counterfactuals. I have done so here in order to make the fault lines visible and palpable. The fact is that no one I know in the U.S. academy considers the terms Cultural Anthropology, Cultural Studies, and American Studies to be synonyms, that is, to refer to the same groups of scholars (at least in the U.S.), and many people I know consider the three to be proper names designating scholarly communities they believe overlap very little, if at all. The irony, of course, is that all three of these communities have a heavy investment in studying “the cultural” and promote cultural studies (this time without capital C or capital S).1 And they do so within a society that most of these scholars now describe as unthinkingly “pro-science” and “anti-humanities” or as too vocationally oriented to appreciate cultural studies. From the outside—or even from the inside in a moment of reflection—one is compelled to ask why the three scholarly circles remain separate nameable entities, and at what cost. And one is tempted to contemplate what benefits could accrue from merging, or at least joining forces.

I speak at an interesting moment in the life of this sector of the U.S. intellectual community, because I believe there is now more overlap, more cross-fertilization, and more curiosity among these three U.S. scholarly circles vis-à-vis each other than in any other period I know in the last decades of the 20th century. Consider, for example, the Editorial Board of the American Ethnologist, long considered the premier journal in cultural/social anthropology in the U.S.. Of the 11 scholars who agreed to serve on my Editorial Board 3 do not hold doctorates in anthropology. One (Arjun Appadurai) self-identifies as an anthropologist but is widely cited in Cultural Studies circles. One (Ien Ang) was primarily trained in Communication Studies and Media Studies but reads cultural anthropology and has written at least two books on the consumption of U.S. television around the world, arguably, hence, in American Studies. And one (Janice Radway) has a doctorate in American Studies, has been a recent past president of the U.S. American Studies Association, but has published two books, both based on extensive ethnographic research.

Consider the content (and the authorship) of two of the past 4 issues of the American Ethnologist, admittedly under my watch as Editor but also much noted and appreciated within the cultural anthropological community both inside and outside the U.S..

Among the published Commentators in Nov. 2003 were American Studies scholars Berndt Ostendorf from Munich and Heinz Ickstadt from Berlin. Likewise, one of the four provocative and moving essays we published in the August 2004 issue, “The Aesthetics of Absence: Rebuilding Ground Zero” (2004), was written by Marita Sturken, then Editor in Chief of the ASA’s journal, The American Quarterly, someone who holds a Ph.D. from the University of California at Santa Cruz in “The History of Consciousness Program” and who I believe is just as comfortable seeing herself as a Cultural Studies scholar as she is an American Studies scholar.

Marita Sturken and I may be somewhat unusual in our increasingly visible tripartite affiliations but we are not alone. Several American Studies departments and programs in the U.S. now also have people with doctorates in cultural anthropology on their departmental faculty roster—from NYU to the University of Texas at Austin to Yale. Performance Studies, an emergent area of scholarship with some institutional programs, publishing venues, and conferences, includes scholars with doctorates in American Studies, cultural anthropology, and other disciplines many of whom identify themselves as Cultural Studies scholars. And the Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, newly reinvigorated and with an expanded Editorial Board, includes several cultural anthropologists besides me (i.e. people located elsewhere in the U.S.) and American Studies scholars like Jane Desmond at the University of Iowa and others elsewhere. Most intriguing to me was a comment made by a very established Communications Studies/Cultural Studies colleague at the University of Iowa earlier this fall (2004) in a very low-key, private conversation we had on the street one day. All I remember is that he looked very surprised when I said something about non-anthropologists rarely coming to anthropologists’ talks (colloquiums), and blurted out, “But anthropology is where it’s at!”

Anthropology is where it’s at? I would like to think so, since I have chosen it as my primary institutional home for the past thirty years, and I have led key institutions in the U.S. anthropological world over the past 5 years, both as President of the U.S. Society for Cultural Anthropology from 1999 to 2001 and as Editor (in Chief) of a newly reinvigorated American Ethnologist since 2002. But too much of the history of U.S. Cultural Anthropology, U.S. American Studies, and U.S. Cultural Studies is marked by suspicion, studied neglect, and even outright antagonism toward one another to make my Communication Studies colleague’s comment ring unproblematically true. And lest one be tempted to say that that was just in the past, consider a conversation I had with a different colleague—this one a self-identified Cultural Studies colleague—at an interdisciplinary planning meeting at a major foundation headquartered in New York about three years ago. Not knowing, or not remembering, that I was a co-founder and co-director, with Jane Desmond, of the International Forum for U.S. Studies, he stopped mid-sentence in our otherwise casual conversation and just proclaimed that American Studies was dead. When I no doubt looked puzzled and challenged his view by noting the thousands of people who attend U.S. American Studies Association Conferences and subscribe to ASA’s journal, The American Quarterly, and the thousands of people around the world who do American Studies and belong to organizations like the HAAS, he became more emphatic, insisting that American Studies was clearly “a bankrupt paradigm.”

At the heart of this messy arena—and of the difficult question concerning the relative degree of suspicion, animosity, overlap, and sharedness among Cultural Anthropology, Cultural Studies, and American Studies—is a brutal fact: that all three use a notion of “the cultural” to study the present (and the past) with an eye to a future that they hope will be better for a society they care about deeply. This means that all three situate themselves deeply within the arena of intellectual scholarly life but have at their very core long been engaged in a kind of cultural politics—one that involves articulating what is not good and needs changing in one’s society, where the locus of the deepest problem lies, and what interventions are most critical. It is, I believe, because choices have to be made about focus, locus, and strategic intervention that suspicion and criticism have greatly overshadowed “sharedness” of purpose.

Indeed, if we look closely at the suspicions, doubts, distance, and critiques that have dominated much of the past 40-50 years as each of these scholarly communities has eyed the other two, what may be most striking is that the significant similarities among them have not typically been enough to generate much cross-over and good will. A decent glimpse of this is evident in data I gathered in the mid-1990s about the professional, institutional, disciplinary identities of scholars with articles published in three U.S. journals widely associated with Cultural Studies: the journal of Cultural Studies itself, the journal entitled Cultural Critique, and the journal Social Text which was later embroiled in a very public (and nasty) showdown about a paper they published which had apparently been a hoax submitted by a scientist seeking to expose Cultural Studies as unscholarly and illegitimate. In all three cases three things are striking: (1) many disciplines appear to be represented (even though the mix of disciplines varied somewhat among the three journals), (2) scholars trained in, or choosing to identify themselves with, English literature or Communications Studies were clearly modal (in the statistical sense), i.e. were the largest single group by far, and (3) very, very few published authors identified themselves with anthropology or American Studies (or American Civilization).

This is too patterned to have been a “fluke.” While one may be tempted to argue that both cultural anthropology and American Studies were much more institutionally established in the U.S. at that time than Cultural Studies—and hence that they already had their own journals and were just not submitting to these three for those reasons, I do not find those arguments convincing enough. For one, American Studies in the U.S. has long been invested in seeing itself as multi-disciplinary, non-disciplinary, or transdisciplinary and its “members” publish in many different kinds of journals depending on the topic or argument of their essays. And cultural anthropology consists of a U.S. population of about 12,000 scholars, the vast majority of whom feel the pressure to “publish or perish” and most of the leading anthropology journals are so selective that the great majority of authors who submit manuscripts are turned down (at least the first time they submit). New-ish journals with the word “cultural” in their titles, or openly welcoming manuscripts from many disciplines (and not requiring or even privileging statistical analyses), should, in principle, have attracted good numbers of U.S. cultural anthropologists. But there is also what we might call “narrative evidence” in professional newsletters and review essays in both U.S. cultural anthropology and U.S. American Studies showing an awareness of something “new” and spreading fast and being visible called Cultural Studies, which in and of itself could lead us to expect more CA and AS scholars to want to become authors in those journals. And, lastly, while some CA and AS scholars clearly depicted Cultural Studies as a threat, or even as anathema, significant sectors of the CA and AS communities and a good number of their leading figures were interested in the phenomenon and not outright antagonistic.

Consider, for example, the following two statements—the first by Marilyn Ivy, then at the University of Washington and now at Columbia, the second by Arjun Appadurai, then at the University of Chicago, now the Provost at the New School (for Social Research) in New York:

NOVEMBER 1993, Marilyn Ivy, Contributing Editor, Society for Cultural Anthropology (column news in the Anthropology Newsletter of the American Anthropological Assn.:

The Society for Cultural Anthropology is organizing a special session, “Culture at Large: Cultural Studies and Ethnography in the US,” at the 1993 AAA meeting. The session reflects on the ongoing exchange between anthropology and cultural studies. Papers are by anthropologists doing research on the US who have abandoned the traditional pursuit of stable, unitary and bounded cultures and are contributing to an ethnographic practice in which the cultural objects represented appear as partly derivative and mutually entangled. Steven Gregory (Wesleyan) critically analyzes the discursive practices that construct the urban poor as a “ghetto underclass;” Catherine Lutz (North Carolina-Chapel Hill) explores contradictions in the visual representation of war to 20th century American audiences, commenting on the powers and limits of cultural studies models; Roger Rouse (Michigan) examines approaches to popular culture which are shaped by the concept of “transnationalism” and considers their implications for the relationship between ethnography and cultural studies. Kathleen Stewart (Texas-Austin) uses an unexpected conjunction between her fieldwork in “Appalachian” coal mining camps and in Las Vegas to address processes of displaced agency and deterritorialized meaning in American working-class discourses. Session organizer Elizabeth Traube (Wesleyan) maps the recent turn toward ethnographic approaches to media audiences and criticizes a tendency to construct “popular” pleasure as autonomous of producing institutions and textual constraints. Judith Stacey (Sociology, California-Davis), author of Brave New Families, will be the discussant. The “Culture at Large” format will be repeated in future years with other themes. (emphasis added)

FALL 1996, Arjun Appadurai in Disciplinarity and Dissent in Cultural Studies (edited by Cary Nelson and Dilip Gaonkar), pp. 28-29:

Debates about cultural studies—seen variously as an area, a field, a program, a discipline, or a conspiracy—reveal an overdetermined landscape of anxieties about the humanities. Two existing disciplinary fields that have much to lose (and also to gain) from the growth of cultural studies in the last decade are anthropology and English and American literature. In general, English departments have been the spaces within which cultural studies has grown and thrived. Recalling the origins of cultural studies in England in the work of Richard Hoggart and Raymond Williams (both students of literature), this is perhaps understandable. . . . As literary critics widened their lens to include all forms of representation, it was natural that the visual world would enter their interests, with its accompanying cinematic, scopic, and feminist critiques. . . . Of course, what looks like a vast and unruly expansion of the subject matter of literary studies in the United States (annually celebrated in the MLA fiesta and demonized by the National Association of Scholars and other conservative organizations) hardly passed without remark within English departments themselves, where scholars of Byron and Chaucer, of Joyce and of Whitman, did not greet this new imperialism of cultural studies without notable alarm and aggressive resistance.

. . . But from the outside, in such fields as anthropology, cultural studies looked like a high-consensus conspiracy by literary scholars to steal CULTURE, or worse, to turn the study of cultural forms into a literary exercise. At this point, the protectionist wing of anthropology joined forces with the literary conservatives to decry, with the usual disregard for detail—all forms of the “postmodern,” meaning all forms of cultural theory which emerged after they stopped reading. This war over culture (tied indirectly to the more publicly discussed “culture wars”) takes on a special displaced force in anthropology, where the last few years have witnessed a growing anxiety about whether and why anthropology should remain the unified home of the “four fields“—socio-cultural anthropology, linguistic anthropology, biological anthropology, and archaeology.

Both of these statements are a far cry from the level of suspicion and even derisiveness one can easily also find elsewhere, especially in the late 1980s and much of the 1990s, and they make any “easy” explanation for the data I showed a bit earlier untenable. It is true that these two statements—by Ivy (on behalf of the U.S. Society for Cultural Anthropology) and by Appadurai—must be placed in the broader context that includes sharply critical and suspicious statements all around—some of which I included in an essay I published in 1996 entitled “Disciplining Anthropology” which appeared in the same book as Appadurai’s essay, Disciplinarity and Dissent in Cultural Studies — and of which the following is a good example.2

MAY 27, 1994—Stefan Collini, Fellow of Clare Hall, Cambridge, and self-identified “Victorianist,” in a review of Fred Inglis’ Cultural Studies and Andrew Milner’s Contemporary Cultural Theory for the Times Literary Supplement, (p. 3):

Here are three recipes for doing cultural studies. First recipe. Begin a career as a scholar of English Literature. Become dissatisfied. Seek to study wider range of contemporary and “relevant” texts, and extend the notion of “text” to cover media, performance, ritual. Campaign to get this activity accepted as a recognized academic subject. Set up unit to study the tabloid press or soap operas or discourse analysis. Describe resulting work as “Cultural Studies.”

Second recipe. Begin a career as an academic social scientist. Become dissatisfied. Reject misguided scientism, and pursue more phenomenological study of relations between public meanings and private experience. Campaign to get this accepted as a recognized academic subject. Set up unit to study football crowds or house-music parties or tupperware mornings. Describe resulting work as “Cultural Studies.”

Third recipe. Identify your major grievance. Campaign to get the study of this grievance accepted as a recognized academic subject. Theorize the resistance to this campaign as part of the larger analysis of the repressive operation of power in society. Set up a unit to study the (mis)representation of gays in the media or the imbrication of literary criticism in colonialist discourse or the prevalence of masculinist assumptions in assessments of career success. Describe resulting work as “Cultural Studies.”

While this may resonate with some of us and amuse others of us at this point in time, the question really is why the venom? Why the suspicion? And why may it be changing now?

Cary Nelson, Paula Treichler, and Larry Grossberg wrote in their introduction to the now classic compilation, Cultural Studies, that “disciplines stake out their territories and theoretical paradigms mark their difference” (1992:1) and that they do so “by claiming a particular domain of objects, by developing a unique set of methodological practices, and by carrying forward a founding tradition and lexicon” (ibid.). When what is at stake is deemed significant enough by its practitioners, the word “different” gets invoked to mean “better,” and the word “distinctive” gets invoked to mean “bounded.” I think these were relevant points then and still now, but they are not sufficient ones.

Over the course of the past ten years I have increasingly come to see the issues as having more to do with what is at stake outside the academy for members of these three (partly distinguishable and partly overlapping) intellectual circles—namely, a desire to have a bearing on life outside the academy—and a disagreement about what to focus one’s energy on, where the locus of “the problem” is, and which intervention is both most crucial and most winnable. In her Presidential Address to the U.S. American Studies Association on November 4, 1993, then President Cathy Davidson both referred to this and illustrated it by using unambiguous exhortatory language to urge the U.S. American Studies conference attendees to focus on shared agendas instead of on the perceived threat of Cultural Studies, “political correctness,” “Affirmative Action,” or “the canon debates.” Some passages are worth quoting from:

NOVEMBER 4, 1993—Cathy N. Davidson’s Presidential Address to the U.S. American Studies Association, published in June 1994, in American Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 2, pp.123-138:

The canon debates have not been fun. They have been mind-numbingly dreary, largely because they have been posed in such simplistic terms. The canon crisis should be leading us to exciting explorations of enormously interesting questions—about periodization, nationalism, identity politics and about how we define and organize knowledge within the contemporary academy. Instead, what passes for curriculum debate in most universities today is scorched-earth guerilla warfare—obliterate everything that is part of any field other than your own. The model is not “political correctness”—whatever that silly term really means. It is political stupidity. The general public reads about the so-called culture wars and wishes a plague on all our houses (pp. 134-135).

And what are we, especially those of us already established in our profession, doing? Are we effectively advocating increased public and private support for education? Are we making clear to the general public just what we do and how well American education actually works? Are we trying to find ways to curtail some of the soaring costs so that higher education remains a possibility for most of America’s citizens?

Mostly we are not. Instead we are engaged in senseless internal squabbling. With so many real crises, it is pathetic to think of so much brain power being wasted on the political correctness debate!

It is all a shell game. While we are bickering over which hand conceals the pea, the barker is robbing us blind. And I mean us. Look at the way the media portray higher education—_all_ of higher education, conservative and liberal, it does not matter. We used to be just a bunch of harmless and irrelevant eggheads. Now we are perceived as vituperative and mean spirited, more concerned with exploiting some square inch of intellectual turf than in preserving education.

Admittedly, the right-wing attacks on academe are debilitating…We all, every one of us, need to be fighting back on every level from the most individual to the institutional. It is tedious, but no more tedious than the futile angst of perceived powerlessness (pp.135-6).

This might have been written 11 years ago (in fact, during the first Clinton Presidency), but it is arguably still relevant and in many ways much more deeply true. On Sunday October 24, 2004, less than ten days before the U.S. Presidential elections this year, I noted with very mixed feelings a long front-page article (published above the fold) by the Des Moines Register, for years considered a model quality newspaper for mid-sized metropolitan areas but now owned by big media conglomerate and considered much more corporate in its orientation. The headline was, “Majority of profs lean left at Iowa schools: A study of the public universities in Iowa shows the faculties have more Democrats.” I asked myself why this was news at all, and to whom. As a trained social scientist, I wondered what data they were using and how the word “left” was being used. I also wondered whether there would be repercussions at the state level, in the state legislature (when budget discussions begin anew), and with alumni giving. I also saw the study of voter registrations, by party, commissioned by the Des Moines Register to be a dangerous sign of the state of “American values” and the dire need to fight for those “values.” Oppositional politics was being reported on and enacted.

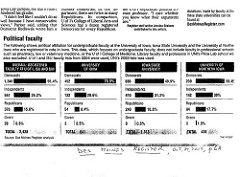

The Des Moines Register explained that their researchers had “matched the names of undergraduate faculty at Iowa’s three public universities with the state database of registered voters to determine professors’ political affiliation. Of the more than 2,400 faculty registered to vote, [it said] 55 percent are Democrats. Independents make up 28% and Republicans about 16 percent” (pp. 1A and 6A). The breakdown by university gave me reason to pause and a suspicion about what the Register was really trying to communicate to its many readers in a state that was in the midst of being covered by the campaigns and the national media as a “battleground state.”

The state’s “flagship institution,” the University of Iowa, did not look split at all. Of the 641 faculty members deemed “undergraduate faculty” at the UI only 54 (8.4%) were registered Republicans. 452 (70.5%) were registered Democrats and 132 (20.6%) were Independents. Put in the national context, Cathy Davidson’s vision that something is very much at stake and that it is really outside the academy, and cannot be ignored by the academy, looms even larger today. Stuck in the middle of the very long article on the “leftist leanings” of Iowa’s university professors teaching undergraduates was the following:

Of the more than 32,000 college faculty surveyed in 2001, the most recent year for which data are available, 47.6 percent considered their political beliefs liberal or far-left, according to the University of California Los Angeles’ Higher Education Research Institute. Eighteen percent of faculty labeled their views conservative or far-right.

. . . Faculty in some disciplines, such as business and agriculture, are more conservative than professors in education or liberal arts, [said Jonathan Knight, director of the Department of Academic Freedom and Tenure at the American Association of University Professors in Washington, D.C.} ISU’s College of Business is the only unit in the Register’s review in which Republicans outnumber Democrats. In that department, there are twice as many Republicans. In comparison, U of I’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences has a dozen registered Democrats for every Republican (p.6A).

In this context—echoed as well in the November 18, 2004, New York Times article entitled “Republicans Outnumbered in Academia, Studies Find” and increasing in visibility in the last two decades of the 20th century, it is worth rethinking the suspicion, the doubt, the critiques, and at times even the wholesale dismissal of Cultural Studies, cultural anthropology, and American Studies by many of those positioning themselves outside any one of these named scholarly communities. It is clear to me that it would be a mistake to attribute any such doubt or negativity to either pettiness or small-mindedness.

Instead, I think it is crucial to understand that, in all three named scholarly communities, a majority of the practitioners hold political (and, yes, moral) stances that they see as contrary to those (intellectual, cultural, and/or governmental practices and paradigms) they regard as numerically dominant in U.S. society. The problem is that in their search for alternatives they have not been so sure who to exempt from “dominant” (enemy?) status, and in the process have frequently come to see in each other a rejected form of oppositional intellectual activity.

Anthropologists, for example, spent much of the 1980s and early 1990s being accused by Cultural Studies scholars of complicity with colonialism and primitivism (even though a long-standing strand of Marxism characterized the work of many leading figures in cultural anthropology who had been trained at Columbia University and the University of Michigan as early as the 1940s and whose students had themselves been involved in 1960s and 1970s Civil Rights, anti-Vietnam War, and “Women’s Lib” activism). Cultural Studies scholars, in turn, spent much of the 1980s and 1990s being accused by anthropologists of paradoxical complicity with elite notions of Kultur because of a perceived enduring textualism (even when extended to graffiti, romance novels, soap operas, or Hallmark greeting cards, and despite the acknowledged origins of Cultural Studies in early 1960s British working-class interventions and its left-leaning sociological politics). And American Studies scholars spent much of the 1980s and 1990s fighting off the charge (leveled at them from both CA and CS scholars) that their collective scholarship (if not necessarily their individual scholarship) remained fundamentally an arm of American nationalism and its still palpable claims to exceptionalism—this despite the fact that most ASA conference programs so highlighted race, gender, and class problems in the U.S. that many 1950s AS scholars in the U.S. and many more AS scholars of varying generations outside the U.S. perceived U.S. “American Studies” to have imploded with only fragments and margins remaining in the spotlight.)

Colonialism, elitism, nationalism, and exceptionalism—perhaps it is the identification of these “no-no’s,” seen as remaining legacies of an imperfect and unjust past in one or more of these scholarly circles by members of the other two, that we should indeed focus on—both as “data” and as hope. Do they not represent the fears, worries, unresolved concerns, or desired limits of, and for, U.S. society in the eyes of a post-WWII, post-Vietnam, and post-Gulf War intellectual community in the U.S. that is not content with current U.S. “values”? In saying this, I am not suggesting that our task should be to point a finger at anyone; rather, it is that spotting these “fractures” in the oppositional culturally-oriented community in the U.S. would be one productive, revealing way to take the pulse and map the shifting landscape of social and cultural critique in contemporary intellectual and political life in the U.S. I, for one, am particularly interested in the fact that three of these four “fracture points” concern the position of the U.S. in the world—“colonialism,” “nationalism,” and “exceptionalism“—and that these concerns long antedate 9/11 and the U.S. led invasion of Iraq. These clearly are not the concerns of a few (or of a marginalized) community in the U.S. In fact, I think that all three named communities—Cultural Studies, Cultural Anthropology, and American Studies in the U.S.—despite a longish history of suspicion, critique, and pursuit (both positive and negative) of each other for decades—may be actually finding in this current political climate that they truly have more in common with one another than they had allowed themselves to see before.

Notes

1 Elsewhere (1996) I have elaborated on this. “In a sociohistorical era that a few of us (e.g. Dominguez, Sakai, White) had, already in the early 1990s, begun to characterize as widely culturalist, it is both noteworthy and unremarkable that more than one intellectual constellation of scholars in the US should have become invested in “culture” and “the cultural” as defining tropes. Proliferation of an objectification of “the cultural” is, after all, one of the characteristics of what I have elsewhere termed global and societal culturalism (cf. Dominguez 1991). The UN participates and promotes a form of it; multicultural governmental and non-governmental discourses exemplify another highly visible form of it; and numerous Fourth World nationalist movements, staking out claims in the midst of those political environments, have likewise embraced the widespread contemporary practice of making arguments in terms of “culture” (e.g. Jean Jackson 1989 ; Roger Keesing 1994).

Skeptics may think that this is window-dressing, that fashionable terms come and go, and that little shared referentiality accompanies this proliferation of invocations of “culture” and “the cultural.” Some scholars are fond of citing evidence of the numerous ways “culture” is used both in and out of the academy: whether it is Kroeber and Kluckhohn whose 1952 collection of over 150 definitions of culture (1952) is cited, or it is Geertz whose 1973 semiotic definition is quoted, or it is Raymond Williams whose Keywords discussion of three “broad active categories of [modern] usage” (1976; see, e.g. John Tomlinson 1991:5) gets referred to, evidence of referential proliferation is not hard to come by. But I want to return once again to Nelson, Treichler, and Grossberg, this time to echo their assertion that, despite Stuart Hall’s often-quoted statement that “cultural studies is not one thing [and] that it has never been one thing” (1990:11), it does matter to practitioners how cultural studies is defined and conceptualized (Nelson et al 1992:3). The incommensurability of many of the referents of “culture”/“the cultural” in actual usage coexists with a high degree of specificity found in the invocation of culture as a sociopolitical act.” ↩

2 One other useful example is from the September 1994 issue of the American Anthropologist, Vol. 96, No. 3, p. 521, written by the then Editors.

There are terrific tensions in anthropology, and we want the Anthropologist to be a place where they can be worked out in a constructive fashion, not in a shoot-out. As A. L. Kroeber pointed out long ago, anthropology has a dual rather than a unilineal ancestry, with the natural sciences on one side and the humanities on the other. More recently, Eric Wolf called anthropology “the most scientific of the humanities and the most humanist of the sciences.” It is no coincidence that anthropologists get grants from both the National Science Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, sometimes for different aspects of the same larger project. But while we have been fighting with one another about what kind of discipline anthropology really is, our neighbors in other disciplines, whether scientific or humanistic, have reached new levels of sophistication in theory and method and have begun to make claims in areas that were once ours to research and teach. It is time we stopped fighting and got on with the work of showing our neighbors on both sides that they haven’t even begun to deal with the full range of human diversity and that no one knows how to do that better than anthropologists (emphasis added). (Barbara & Dennis Tedlock, “From the Editors,” American Anthropologist)

But it is also good to consider juxtaposing this to the measured and thoughtful discussion by Nelson, Treichler, and Grossberg anticipating many of these reactions in their introduction to Cultural Studies (Routledge, 1992:3-4):

While the cultural studies boom is certainly international, its economic value is largely conditioned by its academic expansion in North America; this very success demands that it be closely watched. Will its vitality be compromised by the institutional pluralism of contemporary academic life? Will its rough edges be smoothed out to ease its fit within established disciplinary boundaries? Will the institutional norms of the American academy dissolve its crucial political challenges? What range of work is required to bring about an adequate understanding of what we are doing? What is it that our collective self-clarification must entail? Constructing a vision of cultural studies that can be fruitfully deployed in any particular set of circumstances requires a cultural studies analysis of those very circumstances. At the same time, to address or define the specificity of cultural studies is to ask why it matters. What is at stake in our efforts to practice cultural studies and to reflect on that practice? (emphasis added) ↩

Works Cited

A) Books and Articles

- Appadurai, Arjun. “Diversity and Disciplinarity and Its Discontents.” In Disciplinary and Dissent in Cultural Studies. Cary Nelson and Dilip Gaonkar, eds. New York and London: Routledge, 1996, 23-36.

- Collini, Stefan. “Review of Cultural Studies and Contemporary Cultural Theory.” Times Literary Supplement, May 27, 1994, 3.

- Davidson, Catherine N. “Presidential Address to the U.S. American Studies Association.” November 4, 1993. Published in June 1994 in The American Quarterly. 46(2): 123-138.

- Dominguez, Virginia R. “Disciplining Anthropology.” In Disciplinary and Dissent in Cultural Studies. Cary Nelson and Dilip Gaonkar, eds. New York and London: Routledge, 1996, 37-61.

- Dominguez, Virginia R. “Invoking Culture: The Messy Side of ‘Cultural Politics’.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 1991, 91(1).

- Dominguez, Virginia R. and Jane C. Desmond. “Resituating American Studies in a Critical Internationalism.” The American Quarterly. 1996, 48(3): 475-490.

- Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

- Hall, Stuart. “Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” In Identity: Community, Culture, Difference. J. Rutheford, ed., London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1990.

- Ivy, Marilyn. “Cultural at Large: Cultural Studies and Ethnography in the US.” Anthropology Newsletter, Society for Cultural Anthropology Column, November 1993 issue.

- Jackson, Jean. “Is There a Way to Talk about Making Culture without Making Enemies?” Dialectical Anthropology 1989, 14:127-143.

- Jordan, Erin. “Majority of profs lean left at Iowa schools: A study of the public universities in Iowa shows the faculties have more Democrats.” Des Moines Register. October 24, 2004: 1A, 6A.

- Keesing, Roger. “Theories of Culture Revisited.” In Assessing Cultural Anthropology, Robert Borofsky, ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 1994, 310-312.

- Kroeber, Alfred and Clyde Kluckhohn. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. New York: Vintage Books, 1952.

- Nelson, Cary, Paul Treichler, and Larry Grossberg. “Cultural Studies: An Introduction.” In Cary Nelson, Paula Treichler, and Larry Grossberg, eds. Cultural Studies. New York: Routledge, 1992.

- Stacey, Judith. Brave New Families. New York: Basic Books, 1990.

- Sturken, Marita. “The Aesthetics of Absence: Rebuilding Ground Zero.” American Ethnologist. August 2004.

- Tedlock, Barbara and Dennis Tedlock. “From the Editors.” American Anthropologist (1994) 96:521.

- Tomlinson, John. Cultural Imperialism. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

- Williams, Raymond. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1976.

B) Journals used

- American Quarterly

- American Ethnologist

- Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies

- Cultural Studies

- Cultural Critique

- Social Text

- Anthropology Newsletter

- American Anthropologist

- Des Moines Register

Copyright (c) 2007 Virginia Dominguez

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.