At dusk on a summer evening in 1872 as Walt Whitman drove down New York’s Fifth Avenue, Joaquin Miller—the self-proclaimed “Poet of the Sierras”—rushed out of his door, jumped upon Whitman’s stagecoach and made an appointment to meet with the “Good Grey Poet” the next day (Barrus 74). Over the next two decades the poets developed a friendship characterized by Miller’s dedication to seeking out Whitman and Whitman’s amused tolerance of the younger, enthusiastic Oregonian.

The recent critical recovery of Joaquin Miller’s poetry in several anthologies has been justified on the basis of his engagement with the myths and motifs of the nineteenth century western frontier in spite of his artistic failures, a construction very similar to Whitman’s own assessment of Miller’s rightful place in the U.S. literary canon. In 1871, soon after Miller’s literary success in London, Whitman noted that “Miller… had had the good sense, or luck, to graft. Or get grafted, upon this stock, fresh subjects—miners, hunters etc. from Mexico and California.” Although there “was a dash and spirit in the book, and freshness,” Miller’s first book Songs of the Sierras “would not bear trying by any high, serene standards” (Barrus 60). The terms of these general assessments of Miller’s failure often re-inscribe the value of formal and even national originality that have historically constituted Whitman’s ascendance, the subsequent erasure of the contested status of Whitman and his contemporaries, and the erasure of Whitman’s own inescapable regionalism.

When Paul Crumbley, in the 1996 anthology entitled Whitman’s and Dickinson’s Contemporaries edited by Robert Bain, observes that Miller’s “heavy dependence on the force of delivery suggests some similarity with Whitman, but Miller does not fare well in the comparison” Crumbly succinctly summarizes the current framework in which we understand Miller, his work, and his times (341). His poems, celebrated for their “original” subject matter, proclaimed the unequaled beauty of the Sierra mountains, described love affairs with women “tawny-red like wine,” and celebrated the exploits of giant western men to an audience eager to accept the exaggerated exploits of anyone from the seemingly exotic and foreign ‘Wild West’ (Joaquin Miller’s Poems 30). Both then and now, critics have summarized Miller’s poetry as uneven and picturesque. He is a “local color” poet, a passing specimen of the western frontier, notable for his biographical relationships to the national poets such as Mark Twain and Walt Whitman.

This essay interrogates such comparisons of Whitman and Miller, both in their time period and in our own, assuming that the implications of the comparison are more far-reaching and complicated than the common narrative of aesthetic and historical success. By framing the comparison within the transatlantic framework of Miller’s success in Anglo-British and Anglo-American literary circles and within a transnational, transcontinental framework of the territorial expansion of U.S. peoples and structures of power, the construct of Whitman as a national poet and Miller as a regional poet breaks down. An alternative construction of Miller’s “local color” experiences and the global perspectives in which the poetic mediations of these experiences found voice exposes Whitman’s nationalism as a certain kind of provincialism and Miller’s regionalism as a trenchant example of the construction of U.S. nationalism.

This notion of exposure and the related implication of a disguise will serve as an entry point and a strategy for my reading of Miller and of Whitman via Miller. For Miller’s obvious emulation of Whitman is most successful in his shared impulse to craft his public image as a “rough and ready” poet. The frontispiece of Miller’s collected poetry illustrates the many phases of his carefully constructed public persona with a series of daguerreotypes that culminate in an image that is surprisingly interchangeable with the more famous representations of the “Good, Gray Poet.”

Miller 1897

“Frontispiece to Joaquin Miller’s collected works.”

(From Miller, Joaquin. The Complete Poetical Works of Joaquin Miller. San Francisco: The Whitaker & Ray Co., 1897.)

After describing Miller’s biography and his artful construction of his public identity, I will turn to the poetic construction of U.S. myths of nationalism in several of his shorter poems and the entanglement of these myths and poetic identities in his longer namesake poem, “Joaquin Murieta.” Although Miller can and does stand alone on the basis of his prolific and popular oeuvre, this reading of Miller’s idiosyncrasies, gaps, and narrative breakdowns functions as a distorted mirror with which we perceive the “work” of Whitman’s “disguise” as a poet both transcendent and national.

Joaquin Miller’s Life and Times: Violence without Regeneration

Joaquin Miller’s life and travels resemble Whitman’s poetic catalogs—a list of disconnected and contradictory experiences that span the continent and the globe. A miner and a pony express rider, a poet and a judge, Miller lived and hunted with the McCloud Indians, fought with and against native tribes in northern California, escaped from a jail sentence for horse stealing, married and scandalously divorced a fellow poet, dined with the Rossettis in London, entertained celebrities and statesmen in a cabin outside of Washington D.C., and established an artists’ retreat and amphitheater in the northern hills of California. And yet unlike Whitman’s several poetic lists in “Song of Myself” (“Under Niagra…/ Upon a door-step…/ Upon the race-course…/ At the cider-mill….)—which eloquently evoke a plane of representative experiences available for the reader’s synthesis even as such synthesis depends upon the recognition of jarring distinctions and contradictions—Miller’s biography, intimately tied up with his self-constructed public and poetic personas, offers no such comfortable syncretism.

Named Cincinnatus Hiner Miller, ostensibly for the Ohio town in which he was born, the young poet traveled in a covered wagon to Oregon as an adolescent boy. As a young adult he left Oregon in 1854 and traveled south to California in search of gold, adventure, and perhaps even fame. From 1856 until 1857 Miller camped and hunted with the local McCloud tribe of the Wintu Indians, lived with a Wintu-speaking Indian woman named Sutatot, whom he probably met while she was working on a settler’s farm, and they had a daughter, named Cali-Shasta. In early March of 1857 Miller set out from the valley encampment to find out about a Pit River massacre of white settlers. He was arrested for suspected sympathies with the local tribes and released, perhaps with the understanding that he would join the retaliatory forces, and proceeded to lead white interlopers in the brutal massacre of the Pit River Indians.

Marked by a persistent mix of expiation and exploitation, Miller returns to these early years: his culpability in the Pit River battle and his subsequent return to the white settler communities in California again and again in his poetry and prose. In the “Afterward: The History behind Unwritten History”—an attempt to tease apart historical fact from Miller’s fictionalized but socially-conscious autobiography Life Amongst the Modocs: Unwritten History (1873)—Alan Rosenus describes Miller’s decision to “switch sides” and cast his lot with the white settler and mining forces as the “central expiatory rite of the novel” (58). Miller published, with the support of Mark Twain, his semi-fictional and socially-conscious autobiography of Unwritten History to broad acclaim in Europe, critical condemnation by U.S. literary critics, and successful book sales on both sides of the Atlantic. Detailing the extent to which Miller amplifies, romanticizes, and exaggerates his years spent with the McCloud tribe, Rosenus’s analysis of Miller’s decidedly fictional autobiography can be extended to his public self-presentation and his poetic imaginings as well. Throughout his life and works Miller incongruously fashioned himself as both friend and foe of the native peoples of the North American continent.

Nowhere is this more apparent (and successful) than in his self-constructed public persona as a poetic outlaw: part Buffalo Bill, part Joaquin Murrieta. Although he had published his first book of poems Joaquin et al. to mixed reviews in California in 1869, the outlandish exoticism of his nom de plume, his bolero, his boots, his sash and his Whitmanesque claims as a representative, new poet of a distinctively American stamp secured the attention of the London literati.

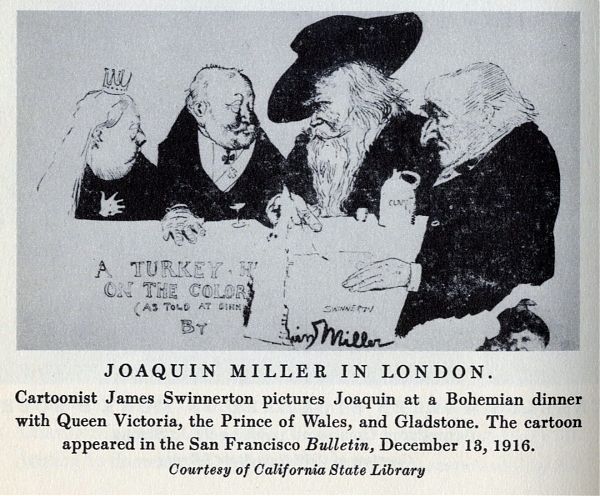

Cartoon from San Francisco Bulletin, December 13, 1916 by cartoonist James Swinnerton that depicts Miller at a “Bohemian dinner with Queen Victoria, the Prince of Wales, and Gladstone” (346).

(From: Walker, Franklin. San Francisco’s Literary Frontier. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1939.)

The recycled publication of several poems that included the long narrative poem “Joaquin Murieta,” under the new title Songs of the Sierras launched his literary career. The legendary Mexican bandit’s name is spelled with two r’s as in “Murrieta,” but Miller used the anglicized spelling with one “r.” I will use Miller’s spelling when referring to the character of his narrative poem, and the Spanish language spelling when referring to the legendary figure.

After this sudden launch into transatlantic literary fame, Miller published poetry, plays, and the above-mentioned semi-fictional autobiography under the pseudonym, “Joaquin Miller,” to varied and increasingly less laudatory acclaim. With the exception of his poem “Columbus,” which students continued to memorize in classrooms across the nation well into the twentieth century, the bulk of his poetry and the legacy of his fame did not survive the turn of the century and the instantiation of the nation’s frontier mythologies.

The palimpsest of two of the most popular and pervasive figures of sensational literature during the time period on the public body of Joaquin Miller, Joaquin Murrieta and Buffalo Bill, initially facilitated his short-lived, transatlantic fame; but ultimately, the turn-of-the-century solidification of the frontier mythologies and the U.S. domination of western territories and peoples would no longer support Miller’s incongruous invocation of the Mexican outlaw, the Anglo-Saxon cowboy-hero of manifest destiny, and the Byronic pose of the Romantic poet.

In his account of Miller’s career entitled “Byron of the Sierras,” Van Wyck Brooks described Miller’s pen name in terms aptly reminiscent of Richard Slotkin’s now canonical analysis of the mythologies of the American West: “Cincinnatus Hiner Miller, like the savage who eats his enemy’s heart in order to absorb his enemy’s virtue, assumed the name of Joaquin Murrieta, well knowing that a bandit’s name commands respect” (240). Although this is an accurate assessment of the success of Miller’s proverbial fifteen minutes of fame, I would argue that Miller was not so successful in this savage rite of what Slotkin has described as the “regeneration through violence” so central to the Anglo-Saxon cultural symbolism of the frontier. In my reading of Miller’s poetry, with close attention to his inaugural poem about Murrieta, it becomes clear the extent to which Miller himself struggled with his failure to synthesize, to inoculate for cultural consumption, his own presence and the presence of native peoples in the actual territories and mythologies of Anglo-Saxon conquest.

In the semi-fictional autobiographical commentary running throughout the footnotes of his Collected Works, Miller remembers with typical overdramatic flair the first time he read Leaves of Grass: “One evening Rossetti brought me Walt Whitman… the last book I ever read. I could not bear any light next morning… nor have I ever looked upon any page long without intense pain…. White paper hurts me…” (Complete Works Vol. 2, 59). Miller’s admiration for Whitman’s innovative verse, so very different from his own tetrameter and often forced rhyme, inspired a debilitating curse in the younger poet (at least in this imagined narrative).

Poetically, it is Whitman who completes the cycle of regeneration through violence—creating something new by dramatizing his engagement with the “primitive” and defying the poetic customs that preceded him. Miller, of course, attempted to fill Whitman’s shoes as a “poetic outlaw,” but did not finally manage. By 1898 Miller’s public persona began to look like the product of smoke and mirrors; by the mid-twentieth century Whitman’s self-construction as the poet of an expanding nation began to take on the weight of cultural and disciplinary fact—an irony of history and cultural considering the extent to which Miller’s actual experiences in the conflicted spaces of U.S. expansion throughout the nineteenth century inform the conflicted spaces of his poetry and prose. Unlike Whitman, who spent most of his life on the Atlantic seaboard but celebrated the plains of Texas and Montana in “Song of Myself” and other poems, Miller’s larger than life persona was fundamentally grounded in the turbulent realities of the American West.

Joaquin Miller, Poet Laureate of the Monroe Doctrine

One can easily read a selected sample of Joaquin Miller’s poetry and conclude that he is an unabashed white supremacist and supporter of unchecked expansion of U.S. territory across the continent and beyond. With the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, and an on-going policy of displacement and removal of Native American tribes, by the mid-nineteenth century the United States assumed economic and political control of vast amounts of land populated by Mexicans and Native Americans. Miller often celebrated this territorial expansion of the United States by invoking the common rhetoric of a mythic Anglo-Saxon race that, originating in England and perpetuated on American soil, was destined to conquer and lead populations. Many of Miller’s shorter and more well-known poems invoke the rhetoric of manifest destiny and the vocabularies of a mythic Anglo-Saxon superiority in their picturesque descriptions of the natural landscape in Oregon and California in rhymed tetrameter more reminiscent of Byron than Whitman.

In 1888 Whitman reflects on Miller as of a type in a historical moment, the kind of “singer, swept into the world, out of the world again… not great or little in themselves, seeming to be in the round-up only a voice to utter the dreams, hopes, faiths, of the people;” perhaps reflecting on himself and his own ambitions as poet: “[I]f you look at it that way the best man is not enough best to be vain of his performances” (in Traubel 139). Whitman recognizes Miller as a voice of the people, a kind of success divorced from performances that are better judged by high, serene standards. While the following three poems support this reading shared by both Whitman and today’s literary scholars of Miller as an emblematic but lesser poet of manifest destiny, the formal construction of the poems complicate Miller’s engagement in the round-up of his subject matter.

The formal contradictions, conflicts, and pauses of these ’exemplary’ poems turn in upon the rhetoric of manifest destiny in a manner resonate with Gretchen Murphy’s description of the rhetorical and cultural status of the Monroe Doctrine in Hemispheric Imaginings: The Monroe Doctrine and Narratives of U.S. Empire. Originally described in President James Monroe’s 1823 State of the Union Address to Congress, the Monroe Doctrine, a contradictory ideology that simultaneously privileged the sovereignty of the nation and authorized U.S. intervention in it’s neighbor nations of the Western hemisphere, remained politically and culturally dominant throughout the later half of the nineteenth century. In addition to exemplifying the Monroe Doctrine’s contradictory impulses of, as Murphy describes it, “identification and disidentification, emulation and revulsion… [and] protection and control,” Miller’s poems foreground the paradox itself (115). Read together, these three poems record an under-story of horror, entrapment, and self-destruction that structures the deep contradictions of the dominant narratives of U.S. expansion and of Miller’s life work.

During the late nineteenth century, thousands of students memorized Miller’s poem “Columbus,” the verbalization of the impulse of a generation to move to what [Miller] sometimes called the “ultimate West.’” The poem is a dialogue between Columbus and “the good mate” who repeatedly questions the adventurer when he should give the command to turn back to the “gray Azores” and “gates of Hercules” (Complete Works Vol. 2, 151-2). With a pounding refrain that must have echoed in schoolrooms across the nation, Columbus responds to each desperate plea, “Sail on! Sail on! Sail on!” Finally, “a starlit flag unfurled” lights the way to the New World, although it is unclear if the sailors have reached land by the end of the poem. This “starlit flag” clearly alludes to the United States flag in a typical jingoistic equation between Columbus’s discovery of the South American continent in the name of the Spanish crown and the establishment of the United States as the nation meant to carry on Columbus’s journey three hundred years later. The poem concludes with a moralizing epithet; Columbus heroically “gained a world; he gave that world/ Its grandest lesson: ‘On! Sail on!’”

This poem could not be more expansionist in tone and meter. Even Miller criticizes it in a footnote to the final collection of his poems as “too much like a chorus.” In addition to the insistence of the refrain, the rhyme scheme and the repetition imbue the poem with a sense of marching forward. Miller embraced and is embraced by the rhetoric of a destined westward expansion on the American continent. But this poem, for which Miller was most well-known throughout the end of the nineteenth century, is not characteristic of Miller’s poetic struggle within the myth of manifest destiny. In many of his poems, and he wrote a very many poems, Miller evokes, teases out, and struggles within the myth of a divine injunction to expand and conquer across the continent and beyond.

“The Missouri,” considered by Miller the better of the two poems in the above-quoted footnote, follows a similar rhyme scheme with repetitive sounds to describe the sweeping of the Missouri river across the continent: “enwound, unwound, inrolled, unrolled,/ Mad molder of the continent!” (Complete Works Vol. 2 153-4). The Missouri River signifies a natural embodiment, “enwound” and “inrolled,” of manifest destiny and the Monroe Doctrine, the movement of United States citizens, goods, and government across the continent’s East-West and North-South axis. Thus Miller’s poetry speaks to the rhetorical and culturally imbedded “balance” between “New World exceptionalism and the embattled dialectics of the Americas” that Murphy describes in Hemispheric Imaginings (2). It would not be a stretch to name the contradictory and conflicted Miller as an apt poet laureate of the Monroe Doctrine. Beginning in the northern territories of the U.S., Miller charts a river path of ownership from “from out an Arctic chine/ To far, fair Mexic seas are thine!” (Complete Works Vol. 2, 153). And yet, deepening the contradiction, even as the first and last stanzas of “The Missouri” unabashedly celebrate the divine destiny of US imperialism, the middle two stanzas unwind the exuberance of the initial verse with a tone and imagery of horror and entrapment. Addressing the river with a series of exclamatory remarks, the “mad molder of the continent” moves recklessly forward,

Yet on, right on, no time for death,

No time to grasp a second breath!

You plow a pathway through the main

To Morro’s castle, Cuba’s plain.

The river—figured in a series of epithets as “Hoar sire of hot, sweet Cuban seas,/ Gray father of the continent,/ Fierce fashioner of destinies” rushes across the breadth and length of the continent, moving south all of the time, with no pause, and creating havoc along the way “states thou hast upreared or rent”(153). The river as father and the river as destiny is out of control. There is an undertone of sensationalist horror in this middle verse that speaks louder than the culminating stanza which returns to the manifest destiny bully pulpit of “Columbus”: “Sweep on, sweep on eternally!”

Miller returns to the methodical meter of repeated exclamations in “Yosemite” with such exaggerated gusto that one questions if he is creating a farce of his own tone (Complete Works Vol. 2, 118-9). Each of the five verses begins with a similar refrain: “Sound! sound! sound!” Fret! fret! fret!” “Surge! surge! surge!” “Sweep! sweep! sweep!” “Beat! beat! beat!” The poem’s sentiments seem to be a restatement of “Columbus” and “The Missouri,” a celebration of manifest destiny that is motivated by the metaphoric appropriation of the sights and sounds of the grandiose natural phenomenon of the West. And yet Miller concludes the poem in the last two verses with the tone of horror and entrapment that erupts in the middle of “The Missouri,” but offers a more coherent critique of this “Gray father of the continent.” Miller manipulates the common belief that the movement west was ordained by God into an accusation that the impulse to advance was forced upon settlers—“loyal, valiant vassals”—against their will by a God that they “may never understand.” The last verse describes an enforced and reluctant conquest that originates out of another culturally resonant story, the expulsion from Eden.

Beat! beat! beat!

We advance but would retreat

From this restless broken breast

Of the earth in a convulsion.

We would rest, but dare not rest,

For the angel of expulsion

From this Paradise below

Waves us onward and . . . we go.

The insistent beat of the opening lines of each verse resound the ominous and threatening command “of the earth in convulsion.” The explication of U.S. imperial policy as the destined, logical outcome of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden masks the role of American agency in the westward movement and absolves all guilt for seemingly endless and destructive advancement. However, this negative embrace of the ordained movement westward is severely qualified by the pronounced ellipsis that ends the poem. This silent pause, so different from the pounding meter discussed above, expresses a profound hesitation to move ever “onward.” “Yosemite” sympathizes more with Columbus’s hesitant mate than Columbus, the seeming hero-conqueror of the New World.

In “Yosemite” Miller captures one of the most enduring and foundational paradoxes of the frontier myth. As long as the myth of the West depends upon the endless impulse to move forward, one dares not stop to rest. To be American is to be always and forever expelled from the “Paradise” gained, eyes always on a more distant frontier: Mexican territories of California, New Mexico, Arizona; French territories of the Pacific Northwest; the Yucatan peninsula; Nicaragua; Cuba, etc. In “Yosemite” and “The Missouri” Miller does not ever question the validity of the destined push westward; his poetry resonates with an awareness of the destructive sweep of lived experience for all that follow the path of mythic Anglo-Saxon superiority.

Joaquin Murrieta, Joaquin Miller, “Joaquin Murieta”

The poem from which Miller took his pen name, “Joaquin Murieta,” is the inaugural form from which he constructed his public personality and perception in London and throughout the United States. It is exemplary of many of his longer poems in its narrative construction, privileged voice of the first-person narrator, and close identification with an extra-literary male hero. Like several of Miller’s other long poems, the mixture between narrative and lyrical poetic forms in “Joaquin Murieta” records the acute entanglement of dominate cultural ideologies and the poetic construction of the individual. In this sense “Joaquin Murieta” offers us an opportunity to read Miller’s construction of the first-person speaker in comparison to Whitman’s better known “omnivorous I.” The narrative breakdown of “Joaquin Murieta” reflects back to us the troubled and cacophonous negotiations that the eloquence of “Whitman, a kosmos” silences. Miller’s inability to seamlessly construct his overt appropriation of the legend of the infamous Mexican bandit troubles (and provides texture to) Whitman’s version of the “American Personality”—capable of absorbing everything and everyone into its Self.

In order to contextualize the idiosyncratic innovations and significance of Miller’s poem I will briefly summarize the legend of Joaquín Murrieta as it was understood in late nineteenth century California. Simultaneously a symbol of resistance to Anglo-American oppression to Mexican miners and an example of the demonization of Mexicans as innate criminals, “Joaquín” was a household name on the West Coast. John Rollin Ridge published his novelized biography, The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta in 1854, one year after the semi-legendary bandit’s supposed death. By 1859 Ridge’s narrative was plagiarized and published to wide acclaim in the California Police Gazette. Presumably Miller was familiar with both versions, although the narrative of the poem seems to agree with the California Police Gazette rendition of events.

In the California Police Gazette version, set in the turbulent years following the end of the Mexican-American war and the frenzy of the gold rush, Murrieta is conceived as a noble-hearted man who only turns to a life of crime after a gang of Anglo-American miners rape and murder his wife, lynch his half-brother, and finally horse-whip him in order to drive him off of his mining claim. After murdering each of the men responsible, his unquenchable thirst for vengeance is turned upon Anglo and Chinese settlers across the countryside. The California legislature issues a warrant for his arrest that leads to a former Texas Ranger tracking down Murrieta’s band, killing the Mexican bandit, and cutting off his head to prove his right to the reward money. The severed head takes on increasing significance as subsequent dime novels, legends, and corridos denied Murrieta’s death and continued to attribute acts of revenge and heroism to him throughout Mexico and Greater Mexico.

Miller’s poem assumes knowledge of the legendary Joaquín Murrieta’s traumatic past and picks up his story with his “reckless ride” from his pursuers. The poem, however, begins with the first-person narrator standing beside “the mobile sea” as the sounds of the ocean become mingled with the sound of the mines and the speaker laments the destruction of the environment and celebrates the “mighty men of ‘Forty-Nine” who first mined the lands for gold. It is only in section II, 81 lines into the poem, that the character of Murieta “rushes on the sight… in terror born on Sierra’s height.” The rest of the poem oscillates between a description of Murieta’s successful flight from the law and the inner torment of the first-person speaker.

Both Miller and Whitman craft strong first-person speakers in many of their poems who alternately assume and dismantle disguises before the readers’ eyes. Walt Whitman’s well-known “omnivorous I” in “Song of Myself” absorbs a seemingly endless succession of momentary identities into the first-person speaker of the long lyrical poem. Section 15 is the most obvious example of this identity construction. Over the course of 63 lines Whitman describes “the pure contralto,” “the carpenter,” “the farmer,” “the lunatic,” “the quadroon girl,” “the half-breed,” “ the bride,” “the opium-eater,” “the President,” “the Missourian,” the “Patriarchs”—to name a few—in a specific moment of action and concludes: “And such it is to be of these more or less I am,/ And of these one and all I weave the song of myself” (76-9). Miller embraces a similar exuberance and strength in his construction of first-person speakers in several of his longer poems. But whereas Whitman’s first-person speaker absorbs the second and third person within an emotive and lyrical celebration of unity in diversity, Miller’s first-person speakers become fragmented in confrontation with third-person characters.

Although ostensibly about the legendary Mexican bandit, the poem is more so a rich and bumbling attempt to consolidate Miller’s many sympathies, heroic ambitions, and actual experiences in California. Emblematic of Miller’s anglicized spelling of Murrieta’s name, dropping the double “rr” of the Spanish pronunciation, the poem is a self-absorbed instantiation of Miller’s own conflicted experiences in the American West. The lyrical self acts as frustrated rival to the mysterious hero in the poem, dramatizing the psychology of Miller’s assumed name and resulting in a powerful climactic image of Miller’s divided self: the lyrical “I” standing precariously upon the other side of a deep chasm that separates him from the heroic Joaquin Murieta.

In this climactic moment the narrator expresses a “fierce impulse to leap/ Adown the beetling precipice” in an echo of the gorge down which the Mexican bandit had just gloriously escaped. This explicit geographical divide between the narrator’s desires and the hero’s adventures characterizes Miller’s curious inability to master the politics of racial superiority and national originality required of a coherent expansionist ideology. The climactic moment occurs as the speaker stands upon the edge of a gorge that “yawns deep and darkling at [his] feet.” He looks away “as from a mighty yawning mouth/ of earth that opens into hell” and then exclaims:

I feel a fierce impulse to leap

Adown the beetling precipice

Like some lone, lost, uncertain star—

To plunge into a place unknown

And win a world all, all my own;

Or if I might not meet such bliss,

At least escape the curse of this.

From where does this “fierce impulse to leap,” to “win a world all, all my own” arise? It is only by becoming “lone, lost [and] uncertain”—assuming the perceived subaltern role of the racialized other—that the western hero can “win a world” all his own. But if this is an evocation of the ambition to conquer, the validity of the speaker’s desire is undermined by the glorious and tragic heroics of the Murieta character, the victim of violent expansionism who successfully descends into the gorge. It is only by defeating the conqueror, the Anglo-Saxon interloper—assuming the perceived subaltern role of the racialized other—that this Anglo-Saxon hero can indeed become a hero.

Although the speaking “I” of “Joaquín Murieta” repeatedly enters and disappears in the narrative, this vexed relationship between the narrator and the hero forms the crux of the first half, if not all of the poem. The “I” of “Joaquín Murieta” is a perplexing blend of omniscience and outside observance. Capable of following Murrieta’s flight across borders and time, the narrator is continually excluded from the action. In his inaugural poem Miller laid the seeds for a revealing distinction between his first-person poetic speaker and that of the “barbaric yawp” sounded from New England’s shores. Unlike the speaker in “Song of Myself” who declares “You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,/ You shall listen to all sides and filter them from your self,” the narrator of “Joaquin Murieta” begins to rely upon only that which the he can see and hear from afar (208). Whereas the first section of the poem describes the speaker standing on the ocean’s edge and daring to “say a prophecy…/ Of rock-built cities yet to be,” the climactic moment of attempted, but failed identification with his hero leaves the prophetic narrator’s vision increasingly obscured.

In the following section, a violent battle between Murieta’s band and the miners is immersed in clouds of dust. The narrator sees the flash of daggers and hears the pistols, curses and prayers of dying men, but the cloud does not lift “like a veil” until not a “sound or word/ Along the dusty plain is heard/ Save sounding of yon courser’s feet.” The lone rider flees toward the dying hero and the section abruptly ends. The narrator watches from afar as Murieta makes his escape and says farewell to a lover, possibly his murdered wife. The observer listens to the whispered conversation between the surreal lovers and although Murieta briefly speaks in the original version of the poem, subsequent revisions maintain the narrator’s exclusion.

I do not heed the hallowed kiss—

I do not hear the hurried vows

Of passion, faith, unfailing love—

I do not mark the prisoned sigh—

I do not meet the moistened eye.

We are once again reminded that the observer is not the hero. The narrator’s inability to make such a leap and extend his vision operates upon the failure to fulfill the desire to be both hero and narrator. The narrator, a poetic prophet, is left stranded on a ledge of exposed confusion and compromise. Whereas the emotional and inspiring eloquence of Whitman’s “Song of Myself” silences the discord of diversity through the construction of an empathetic narrator who privileges unity and harmony over verbalized irreconcilable conflicts, the troubled voice of Miller’s narrator exposes the often ignored violence that underwrites this impulse to equate diversity with unity.

The rest of the Joaquin, et. al. version of “Joaquin Murieta” was revised in the London edition and omitted in its entirety from other versions of the poem included in both of Miller’s self-collected works, but it is in this second denouement that the narrative structure dissolves into an entirely different narrative from the well-known Murieta narrative of the corridos and the dime novels. The narrator turns his gaze upon a jungle and a battle between “a Hapsburg King” and “Aztec” soldiers in the “Land of the cactus and sweet cocoa,/ Richer than all the Orient.” Miller romanticizes the Murrieta legend through a variegated and confusing description of his hero’s racial and national background. This Murieta is not the clear-cut symbol of Mexican resistance to Anglo oppression that the legend would later become for the twentieth century Chicano movement. Initially depicted with a fair complexion and long, dark flowing hair, Miller transforms Murieta into the heroic descendent of Montezuma who returns to Mexico to defend his people’s land there. Miller’s characterization of Murieta as both a Mexican bandit “whose fair face is/ Still holy from a mother’s kiss” and an Aztec directly descended from the noble line of Montezuma embraces the confusion that surrounded the status of Mexicans in the newly acquired U.S. territories. The landowning aristocracy explicitly privileged their Spanish decent over the Indians and mestizos that traditionally served them in the hacienda structure.

The amalgamation-fragmentation of the mythic characters—Murrieta of Greater Mexico, Montezuma of ancient Mexico, and the first-person speaker of the US West—offer us a productive, if bizarre, dissonance on the level of plot. Montezuma’s heir, whom we later learn is Murieta returned to his homeland to defend “Montezuma’s throne” from the French, is carried off of the battle field to a small grey church. The Indian chief, the infamous Mexican bandit in previous years, bemoans his tragic past and summons the energy for a dying diatribe against conquest and Catholicism that he claims is responsible for the death and disappearance of his people.

The Montezuma-Murieta figure warns the priest watching over him that if he crosses himself one more time he will kill him. The chief recounts his first battle with the “Saxon,” a slaughter from which he and the Indian woman escaped to a secret lake and then fled north to a worse fate, the lynching, whipping, and rape episodes of the Murieta story. He tells the priest that he wandered in a living death “o’er many a realm” until compelled to fight for his people in Mexico. Throughout the monologue, the priest continues to cross himself and Montezuma-Murieta finally stabs him with his last remaining breath.

Thus, the legend of Joaquin Murrieta transforms into a weird amalgamation of the Murrieta legend, the fall of Aztec Mexico and the French invasion of Mexico in 1867. The lyrical self does not appear again until the culmination of the poem, affecting a kind of self-erasure that operates as an inverse to the erasure of other voices as they are silenced by the empathetic narrator in Whitman. Although this awkward narrative transformation is not intentional, “the oscillation between conformity and incomprehensibility [is] strangely productive” (Wald 3). Similar to Priscilla Wald’s analysis in Constituting Americans of four American authors who intentionally disrupt their literary narratives in order to expose the limitations of accepted literary forms and to tell the stories denied verbalization by the dominant national ideology, the narrative and character fragmentation of “Joaquin Murieta” exposes the contradictions and limits of the Whitmanesque lyrical poem and the celebration of diversity in unity. Clearly, Miller did not purposefully trouble his narrative poems in a conscious effort to revise and complicate dominant national ideologies, as he perpetuated them so profoundly in his person. However, we can read even Miller’s unconscious “disruptions in literary narratives caused by unexpected words, awkward grammatical constructions, [and] rhetorical or thematic dissonances” as creative reflections and distortions of known stories; in this case the known story of Whitman’s effulgent lyrical persona as intimately tied to the sense of a coherent, unified United States (Wald 1).

It is tempting to resolve the dissonance of this narrative turn with a reading similar to Murphy’s analysis of Lew Wallace’s novel A Fair God where Miller is a cultural representative of the Monroe Doctrine. The transformation from Murieta to Montezuma effects an explicit if weird identification of the democratic, Protestant virtues of the United States with the democratic virtues of native Mexicans defending their country from the Catholic French monarchy. But to the extent that this is so, Miller fails in his construction of this culturally powerful rhetorical gesture. The compelling significance of this poetic denouement is that Miller tried to write such an unconvincing transformation and failed to do so.

Montezuma-Murieta describes the return of his people after centuries of tyranny under Spanish “troop, and king and cówled priest” with implications that should be understood in light of the Monroe Doctrine rhetoric of a shared defense of democracy in the face of tyranny. But the terms of Montezuma-Murieta’s monologue become confused and the backdrop of Miller’s narrative construction is revealed as not only the register of a national foreign policy but also the domestic realities of conquest in U.S. territories. After describing the Catholic conquest of the Spanish, Montezuma-Murieta exclaims to the priest:

But useless do I prolong

The tale of tyranny and wrong,

Well known to you as ‘tis me.

The Saxon came across the sea

With gory blade and brand of flame.

I know not that he knew or cared

What was our race, or creed, or name;

I only know that the Paynim dared

Assault and sack for sake of gain

(Joaquin et al. 38).

As a signifier for the Mexican and the Native American in U.S. popular culture, the Murieta-Montezuma figure becomes in Miller’s construction a consolidation of the oppressed and silenced Native Americans and native Mexicans in California and Oregon whom Miller ineffectually wished to defend and to give voice throughout his career. He manipulates the legend of the Mexican bandit’s vengeance into his platform for decrying the dispossession and decimation of native tribes, in an act of self-absorbed expiation and exploitation similar to his above-mentioned fictionalized autobiography, Life Amongst the Modocs: Unwritten History.

Within the course of this unwieldy plot the character of Joaquin Murieta turned Montezuma and the troubled and limited characterization of the narrator suggest but ultimately cannot synthesize the overt signifiers of the Anglo-Saxon cowboy-hero of the U.S. American literary tradition, the racialized other as Mexican, the racialized other as Native American, and the Byronic hero of the British literary tradition. Both in the language of the poem and the publication journey of this inaugural poem and its author, London becomes a central space in which Miller’s poetic acts of exploitation and expiation find voice. Thus, Miller engages the dominant myths of an Anglo-Saxon cultural and race, based in the often denied deep cultural ties between the US and England, within a space of violent cultural contact in the North American West and Southwest. This almost schizophrenic, always conflicted embrace of a transatlantic and a transcontinental worldview prompts Whitman to give him his most apt and perhaps most generous epithet as a “California Hamlet.” On this occasion Whitman described Miller as “mopish, enuyéed, a California Hamlet, unhappy every where—but a natural prince” (Barrus 74). It is within this high stakes nexus between the transatlantic shadow of the past and the manifest destiny of an American future that Joaquin Miller most threatens the elder poet’s disguise. Citing Richard Slotkin, Robert Weisbuch in Atlantic Double-Cross: American Literature and British Influence in the Age of Emerson observes that “the west myth raises the bet on the success and failure of American literature to an all-or-nothing, heaven-or-hell proposition” (75). The British embrace of Miller’s engagement with the myths of the American frontier troubles Whitman’s own dialectic between the old and the new, the British and the American—a dialectic that he continually structures as incommensurate. The unresolved entanglements of the American cowboy-hero, the racialized other as hero, and the Byronic hero in “Joaquin Murieta” expose the Whitmanesque lineage from a magnificent American landscape and people to an organically American poetic and political democracy as itself a construction.

The overly dramatic death of the chief-bandit (“I thrust—I fail—I fall—I die—”) is followed by a hauntingly Byronic conclusion that further attests to Miller’s inability to resolve the cultural registers from which he so liberally drew his art. In the last section of the narrative the speaker stands on the site of the battlefield years afterwards, resuming his role as poetic-prophet and overseer. But the speaker soon fades to the background and returns to the still-standing old grey church. The church has been abandoned by everyone but the ghosts of Montezuma-Murieta and the Catholic priest, “One worships Christ by night, and one/ By day is worshipping the sun.” Far from reconciled, the two ghosts haunt the same abandoned building at different times of day, bound to each other but forever disconnected. Miller gives us one final tableau of his “ultimate west”: housed in the seemingly benign structure of a rural church the ghosts of two cultures live on in torment, worshipping their own gods side by side but without reconciliation.

Conclusion

In letters, published commentary, and published prose, both Miller and Whitman construct their relationship in terms of a generational inheritance: a son to his father and a student to his teacher. For example, in a letter addressed to Walt Whitman and dated September 1871 Miller signs: “The grandest and truest American I know, accept the love of your son, Joaquin Miller” (Traubel 107). And although Miller certainly sought Whitman out as a teacher and father-figure—much to Whitman’s alternating chagrin and amusement—Whitman returned the sentiments often enough in his correspondence and conversations about the younger poet. In one recorded conversation between Whitman and Traubel, Whitman seems to admit this allegiance in spite of himself, “I guess I belong to Miller: he has proved himself in so many ways—his books have proved him, his personal affection has proved him” (57). Re-reading Whitman through Miller’s failure as his self-styled student allows us to establish a plane of comparison that derives from Whitman’s own poetic project and not from the historical or critical terms of success and failure.

Published in the 1860 Leaves of Grass and then again in 1867, Whitman poses a question addressed to a hypothetical student (Whitman uses the French term eleve) in “To a Western Boy”:

Many things to absorb I teach to help you become eleve of mine;

Yet if blood like mine circle not in your veins,

If you be not silently selected by lovers and do not silently select lovers,

Of what use is it to become eleve of mine? (166)

Written before the 1871 success of Joaquin Miller’s Songs of the Sierras and therefore long before Whitman had heard of Miller, “To a Western Boy” establishes one possible interpretation of the “high, serene standards” that we might read in Miller’s failed emulation of the elder poet.

Whitman’s prophetic voice, his “barbaric yawp,” often figures as a counterintuitive whisper, a noiselessness, a silence. In “The Sleepers” the narrator wanders among sleeping husbands and wives, dead and living, master and slave, “stepping with light feet, swiftly and noiselessly stepping and stopping” (440). The “barbaric yawp” that Whitman describes as “not a bit tamed” and “untranslatable” in “Song of Myself” is most characterized by a necessarily silent and voiceless collusion between poet and reader, man and women, friend and foe (124). “Song of Myself” is an example of this “aesthetics of democratic prospects” where everyone and everything is brought “simultaneously to the same plane of representation” as described by Philip Fischer in “Democratic Social Space: Whitman, Melville and the Promise of American Transparency” (110). The emotional exuberance of Whitman’s tone and free verse paradoxically depends upon a foundation of “silent selection.”

Miller ultimately fails as a representative of this wild American originality because his selection of lovers and loyalties continually erupts in conflict and irresolution. The emotional exuberance of Miller’s tone and metered verse, the distorted mirror of Whitman’s eloquence, evokes a sense of horror, haunting, and entrapment that is a result of his inability to silence the contradictions of myth and reality, art and lived experience in his “ultimate west.” What Whitman eloquently and therefore silently subsumes into himself and his songs, Miller awkwardly but passionately voices—the historical realities of the nineteenth century development of the nation and the complex dependency of a cohesive American identity upon racialized others.

The implications for this reading of Miller’s poetry in light of Whitman’s poetic legacy offers a new reading of the construction of the national and the transcendent so important to Whitman, his literary peers, and the disciplinary history of U.S. American literature. Whitman’s poetic voice—as it so wonderfully celebrates a mystical and spiritual unity that defies all hierarchy in favor of humanity, life, essence—soars into the realm of the spiritual on the tails of an engagement with the national expansion westward, an engagement that demands an appropriation of the fellow humanity of others even as it desires to proclaim it. “Walt Whitman, a kosmos” must actively construct all other identities—particularly the conventional racialized others of nineteenth century US nationalism—as subsumable into his self.

Miller’s poetry and literary career questions and troubles these hegemonic, Anglo ideals of an original and inherently American unity, one which transcends transatlantic and transcontinental influences, as it was articulated and bequeathed by Whitman to American letters and culture. By returning to the early 1870s when the overt signifiers of Miller’s assumed name “Joaquin,” the troubled contents of his poetry, and the conflicting loyalties exhibited by his life and work spoke just as loudly as Whitman’s songs of national unity, we upset the easy designation of Whitman as national poet and Miller as a “local color” poet. One can undoubtedly see Whitman’s particularly influential brand of nationalism, which I have here referred to as diversity in unity, as divorced from the violent realities of the nation-making project of the nineteenth century. By placing these two poets and their works within a comparison configured by Miller’s conscientious emulation of Whitman, the literary milieu they shared and the nonliterary worlds they did not, Miller’s alternative voice of American selfhood compliments and corrects New England Romanticism’s legacy of a transcendently “American” literary and national story.

Works Cited

- Barrus, Clara. 1931. Whitman and Burroughs, Comrades. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Brooks, Van Wyck. 1932. “Byron of the Sierras.” Sketches in Criticism. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc.

- California Police Gazette, Joaquin Murieta, the brigand chief of California: a complete history of his life from the age of sixteen to the time of his capture and death in 1853. 1932/1861. San Francisco: Grabhorn Press.

- Fischer, Philip. “Democratic Social Space: Whitman, Melville and the Promise of American Transparency.” Representations, Fall 1988: 24.

- Frost, O. W. 1967. Joaquin Miller. Twayne’s United States Artist Series. New Haven, Conn.: College & University Press.

- Horseman, Reginald. 1981. Race and Manifest Destiny. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Lawson, Benjamin S, Jr.. 1980. Joaquin Miller. Boise, Idaho: Boise State University.

- Miller, Cincinnatus Hiner. 1869. Joaquin, et. al. Portland, OR: S.J. McCormick.

- _________. 1872. Joaquin, et. al. London: John Camden Hotten.

- Miller, Joaquin. 1897. The Complete Poetical Works of Joaquin Miller. San Francisco: The Whitaker & Ray Co.

- _________. 1975. Joaquin Miller’s Poems. Vol. I-VI. New York: AMS Press.

- _________. 1871. Songs of the Sierras. Boston: Roberts Brothers.

- _________. Unwritten History: Life Amongst the Modocs. Hartford: American Publishing Company, 1874.

- Paz, Irene. [1925] 2001. Joaquin Murrieta, California Outlaw. Houston, Texas: Arte Publico Press.

- Ridge, John Rollin. 1854. The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta, A California Bandit. By Yellow Bird. San Francisco: W. B. Cooke and Co.

- Rosenus, A. H. May, “Joaquin Miller and His ‘Shadow’.” Western American Literature: 1976, XI.1.

- Slotkin, Richard. 1973. Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860. Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Traubel, Horace. 1908. With Walt Whitman in Camden. Vol. 1-4. New York: D. Appleton & Company.

- Wald, Priscilla. 1995. Constituting Americans: Cultural Anxiety and Narrative Form. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Walker, Franklin. 1939. San Francisco’s Literary Frontier. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Weisbuch, Robert. 1986. Atlantic Double-Cross: American Literature and British Influence in the Age of Emerson. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Whitman, Walt. 1996. Walt Whitman: The Complete Poems. Ed. Francis Murphy. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Copyright (c) 2010 Jill Anderson

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.