Introduction

The study identifies and analyses a series of stereotypes regarding the image of the Other (the Enemy, symbolised by the US) as presented in political cartoons published in the mid 1940s- early1950s Romanian press (especially cultural magazines – such as Flacăra, Contemporanul - or comic almanacs, where they appear massively, but also, in a less important number, in the official newspapers). The study focuses on the means used by political propaganda to construct, trough artificial (distorted, exaggerated) images – the political cartoons – a typology of an “invented enemy”. This abstract constructed identity is placed within a Manichean formula: the Romanian (communist) versus the American (imperialist), which are themselves abstract, artificial propaganda representations. Political cartoons are an interesting propaganda tool, trough their hybrid specificity (mixing amusement – or actually hiding behind it – with political serious matters). Thus, they play a unique part among the instruments used by totalitarian propaganda and in general within the Cold War, because this innocent appearance covering a subtle form of manipulation.

The historical context, in which the analysed images were published, was a difficult political moment for the Romanian society, because of the emergence in the late 1940s of a Communist totalitarian regime. As these images are part of the larger political propaganda, it is interesting to see how the regime used – trough the press it controlled entirely – even the aspects considered to be innocent or without importance such as cartoons or caricatures. The moment is eve more illustrative because the Communist regime was at its beginnings in Romania and therefore needed very much propaganda (at all levels), press and image manipulation in order to legitimise its existence. As communism came to power without support from the population, persuading them into believing the official truth was a priority. Under direct Soviet influence (it is a moment when the URSS influence is extremely powerful and the press of the time reveals it through texts and images) and with the main help of the press, the “new” pattern (new society, new man, new ideology) was to replace the “old”, bourgeois counterpart and therefore perverting the image of Western societies (especially the US) and their values (as associated to the former society). Julia E. Sweig speaks on anti-Americanism (as a problem of the 20th century) in the Cold War context emphasising on the one hand the anti-American effects of the rivalry between US and the Soviet Union and on the other hand of the ambivalence of some countries in relation to the American power (31). Even if she speaks of this ambivalence when speaking about Western European countries, this can also be applied to some Communist countries, as there is a gap between the negative image the official discourse constructs and the real perception of people. The Romanian people were particularly affectionate to the Western allies, among which the French were the traditional ally while the American were perceived as potential saviours (see the myth of the Saviour in Raoul Girarded’s classification of political myths). Therefore, the US, as a symbol for all that was typical to Western, non-communist societies, had to be transformed trough the means of official propaganda into a complex of negative stereotypes (an “imaginary enemy” as Ştefan Borbély calles it or ”a false enemy” in Joanna Witkowska’s words, see their studies on the topic).

Fig.1. Title: Renovating the Statue of Liberty in the US

The construction of this abstract identity of the enemy (symbolised by the US) was achieved by different means, but the use of visual materials was considered the most powerful, even in a period when limited means were attached to image reproduction or transmission.) The visual message is one of the most powerful means of propaganda, because of the immediate, especially emotional, impact (before the appearance of television propaganda consisted especially I political posters, caricatures, drawings). The drawing was even more significant than a photo, especially because it meant creating, shaping an image, exaggerating or eliminating features, not copying a reality (which might not have been convenient). Later, when photography evolved and started to occupy a more important place in printed press, the modified photos became very common during the Communist regime, their processing meaning especially adding or eliminating people from the photo on political grounds (for instance, whenever someone, usually a politician, became undesirable he/she was eliminated from the official photos and newspapers were forced to take this into consideration and publish only the officially approved variants of these pictures).

Images in Propaganda. General Issues

The propaganda discourse is considered partly similar to advertising, because they are both focused on emotional impact while information is secondary (Roşca 168). Ironically, communist press and Western advertising were both “selling” emotions and colourful illusions, although the end was different, as the totalitarian regime “sold” to the viewer or post-war “consumer” the processed (artificially constructed) image of an enemy and aimed to induce a complex of negative feelings attached to the perception of this image.

Fig. 2. Title: “His Politics”. Text: “Truman: ‘My’ politics is pacifist.”

While the press discourse has the role to be first of all informative, in totalitarian regimes this function remains secondary, while the role of the propaganda discourse becomes precisely the opposite: to misinform, to persuade the reader to believe in a construct called “truth”, although the latter is a fiction, created on ideological grounds. The mirror is reversed: any other “truth” outside these artificial boarders (created by a “misinforming” press discourse) would become a lie of the enemy, a mystification of “our” (read: totalitarian) truth. Many of the images analysed in the current study have in the centre this opposition between “our” and “their” truth. The idea of opposition between “us” (the Good one) and “them” (the bad) [see also fig. 24 below] – between the two types of societies described in a Manichean formula – lies in fact at the basis of this propaganda discourse, with its persuading techniques, press being an essential factor in every conflict and even more in a post-war society such as the Romanian (governed by a newly installed totalitarian regime).

Fig. 3. Title: Candidates and “Candidates”. Text: 1. It is no accident he was named a candidate for the Supreme Soviet in URSS: the foreman has golden hands. 2. It is no accident he hopes for a place in the American parliament: he has his hands in the gold.

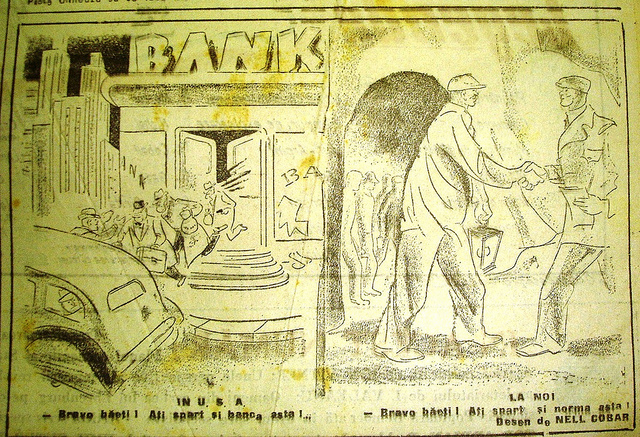

Fig. 4. Title: 1. In the USA. Text: “Well done, my boys, you broke this bank too!”, Title 2. In our country. Text: “Well done, my boys, you broke this standard too!”

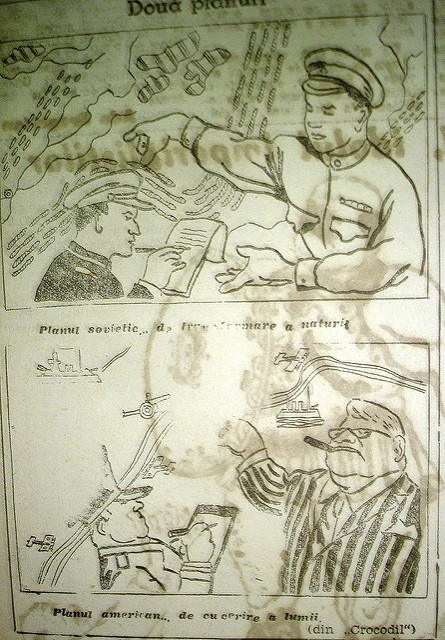

Fig.5. Title: Two Plans. 1. The Soviet plan of transforming nature. 2. The American plan of conquering the world.

If we consider this extreme opposition proclaimed in all respects while associating the Other, the “enemy” with absolute evil, no wonder that the press controlled by the totalitarian regime fights (a press cliché of the time) against an enemy, an abstract yet complex identity well defined through a complex of stereotypes. Justified both by the Marxist-Leninist ideology and partly by the fact that we speak of a post-war period, the idea of fight was present everywhere in the late1940s-early1950s Romanian periodicals, no matter if in articles, images or literary piece of work and seems to be a constructed symbol of the “new” Communist society.

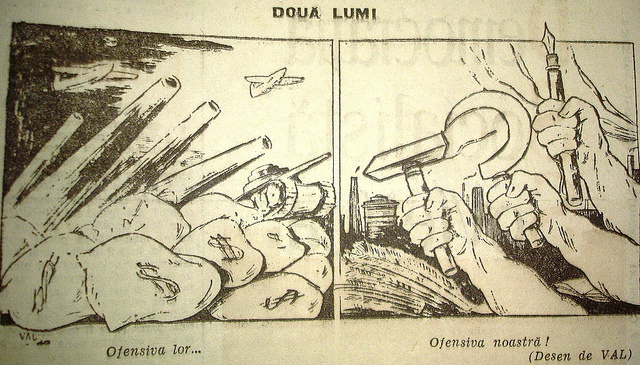

Fig.6. Title: Two Worlds. Text: Their offensive…Our offensive!

Political Cartoons – A Specific Form of Propaganda Discourse

Illustrating in a very a very interesting and accentuated way this opposition the regime wanted to induce to the people (“us” versus “them”, Communist block versus US and allies), political cartoons are a very specific form of propaganda discourse in the Communist press of the period, not only in Romania (see below, the use of the same means by both parties). Involving manipulation as a form of strong persuasion, political propaganda within totalitarian regime means intentionally distorting (Roşca 170), both one’s own image and the other’s image. As the idea of distorted image is probably most obvious precisely within political cartoons (exaggerating some features, eliminating or accentuating others) they become a very special means of transmitting this highly subjective propaganda message without trying to simulate objectivity or lack of bias. Moreover, the image transmitted by the political cartoon was a privileged tool for Communist propaganda because of its symbolic and affective implications, as well as its humorous appearance, transmitting a hidden message.

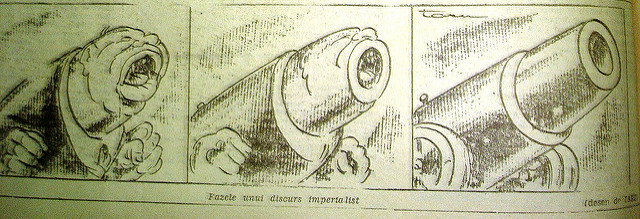

Fig. 7. Title: The stages of an imperialist discourse.

When comparing a numerous amount of such images (see classification below, Table 1.), as intended by the current study, the most obvious observation is the fact that they contain a series of recurrent suggestions, imposing a set of clichés (at the level of the characters depicted, issues, symbols and so on). The present study will analyse these stereotypes and common topics and features present in the political cartoons, trying to establish which the dominant ones are and which was the motivation of their extensive use, which political symbols and characters are present and what elements of the political context determined the propaganda to emphasise certain ideas and characters more than others.

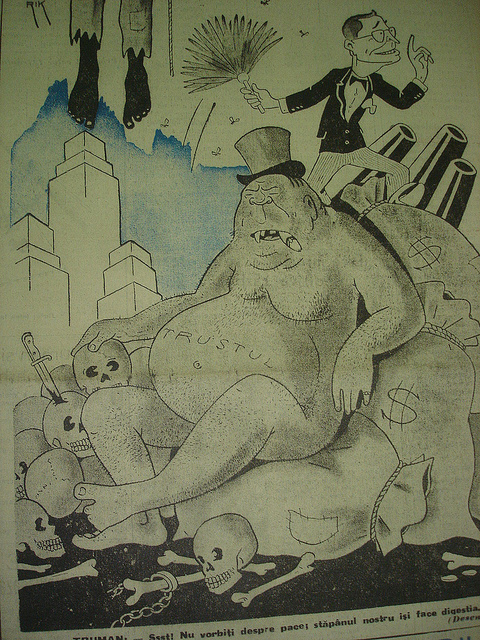

Fig. 8. Text. “Truman: ‘Silence! Don’t mention peace: our master makes his digestion.”

We can speak of these political cartoons as parts of a form of fiction: propaganda being the framework of the creation of a set of illusions and symbols, characters and roles, of constructed and controlled “truths and “believers” (almost in a religious manner, see below the attempt to discredit and replace religion with the Communist “creed”). I mentioned propaganda and particularly press as forms of “controlling truth”: the regime created a complex system of persuading and control means in order to reach the minds and emotions, education and will of the receivers of the “information”. The purpose was to make them react as expected, by maintaining them passive to some aspects while “mobilising” them towards others, but especially to control and filter what information reached them. “By monopolising information, the Power creates and distributes a bastard entity, a mixture of partial truths and credible lies, of reality and illusion, said and presumed – this hybrid product is [emphasise added] official information.” (Coman 134).

Fig.9. Title: “This is America!”

Propaganda represents therefore a very specific form of communication and social role distribution. Another level at which one can also read propaganda discourse is as a convention (both politically and socially based) regarding persuasion and belief (the “organised lie” as Vaclav Havel called it). Joanna Witkowska writes about the Communist ”fighting for the minds of people” but even if the purpose was real persuasion, Romanian propaganda started as and remained until the end of the regime (in different versions) a convention. This meant both writer or reader, transmitter or a receiver of propaganda texts or images assuming a role (very well organised, planned) in a rigid structure. Rigidness also meant controlluing the quantity of information: the latter was rationalised, given in small quantity and only under the monopoly of the official propaganda, in opposition to the Western societies, where the information (of any kind and from any field) is abundant (Mattelart, qtd.in Coman 134) as the media (TV channels, newspapers, magazines and so on) are also numerous. The same rigidness also involved (as a very important element) a stereotypical language (repetitive and using the same “safe” formulas) and message.

The stereotypical characteristic is maintained even beyond the propagandistic written formulas, in images (particularly drawings). Here, especially when speaking of political cartoons, the persuasion takes the appearance of innocence and tries to hide the political message in an interesting and attractive form. Thus, political cartoons play their own role in the propaganda system of the Communist regime and are even symbolic in the way they approach (through satire and humour) the conflict with US and Western values, filtered by the recently (then) finished military conflict.

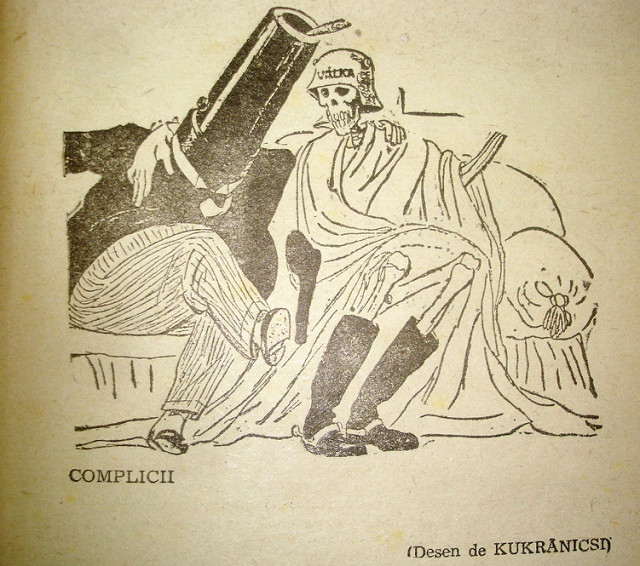

Fig.10. Title: “The Accomplices”

As Ştefan Borbély argues (2002, 138), the negative aspects of a conflict and particularly the atrocities of the war are always associated with the Other, the enemy, a image opposite to the complex of features “we” define as “ours”, creating the image of an (always positive) identity. This Manichean approach when defining one’s identity in opposition to another, a different one, guilty of all the disasters (especially within a military conflict) characterises human image structures (l’imaginaire) in distinct societies. This feature was exploited and stimulated in totalitarian regimes when the image of an abstract Other represented a controlled target of all the social frustrations. Press (a sort of “organ of speech” of the Power), was the channel through which the regime would transmit this political creation of the Other. Distorted par excellence by distance and difference (“the Other is most often a real person or community, observed however through the deformed filter of the imaginary [emphasis added]”, Boia, 2000, 117), the distortion is much amplified (in an intentional, very well organised manner) within totalitarian regimes. Here the information (on the Other) is, as stated below, insufficient and rationalised, while the intention is to create or redirect and then manipulate the potential negative feelings towards the Other. Functional or not within the mentioned social convention, this constructed identity of the enemy is however most interesting (in its fictionalising mechanisms) when referring to actual propaganda tools such as images in the politically controlled magazines and newspapers of the late 1940s-early1950s.

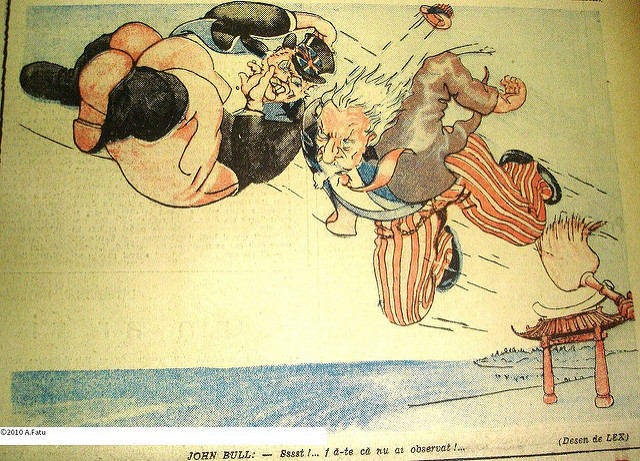

Fig. 11. Text: John Bull: “Pretend you didn’t notice!”

Stereotypes in the Construction of the Enemy

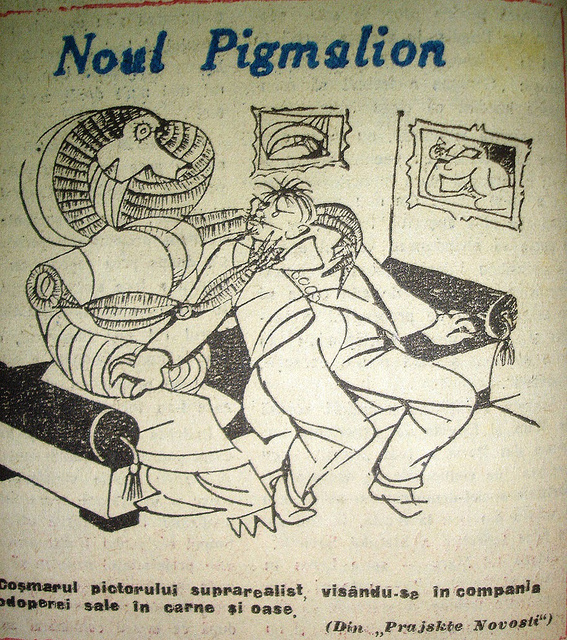

Romanian propagandistic political cartoons in the period approached by the current study has mainly two complementary features: the first is that they emerge under a strong Soviet influence (recognisable if comparing the Romanian and Soviet images, while some are even reproduced from URSS periodicals). This can be explained in the political context, when Soviet control existed at all levels and it is obvious that propaganda (with its importance already emphasised above) was an important aspect in this context. The Soviet “model” is an explicit one, as it is obvious from instance from a short article written (after a Soviet cartoons exhibition in Bucharest) by a Romanian artist (who signs many pictures analysed here), signing RIK. Using some language clichés of the time (present in all articles, no matter the topic, from industry to art), such as the Soviet as a “great example to follow” even in cartoons, the author openly emphasises in an interesting manner the propagandistic role of cartoons, which are a “weapon against imperialism”, and must be characterised by realism and “critical representation of reality” (Flacara, 1949). As stated below and obvious in many images, “realism” was the only accepted style, while modernism or the style of the avant-gardes is associated with a decadent (and decaying) culture which Communist artist should fight against.

Fig. 12. Title: The New Pygmalion. Text: “The nightmare of a surrealist painter, dreaming of himself accompanied by his flesh and bones muse”.

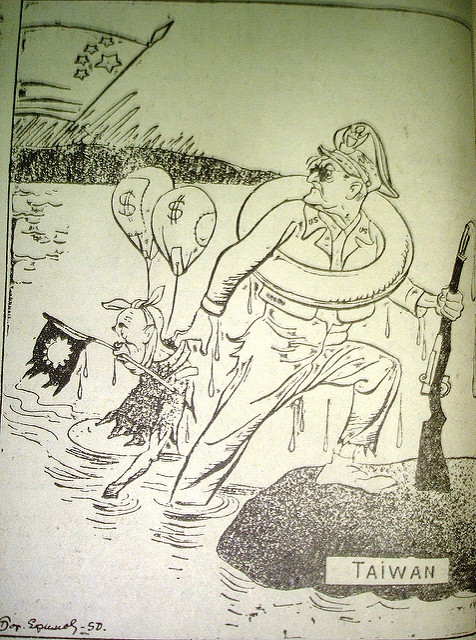

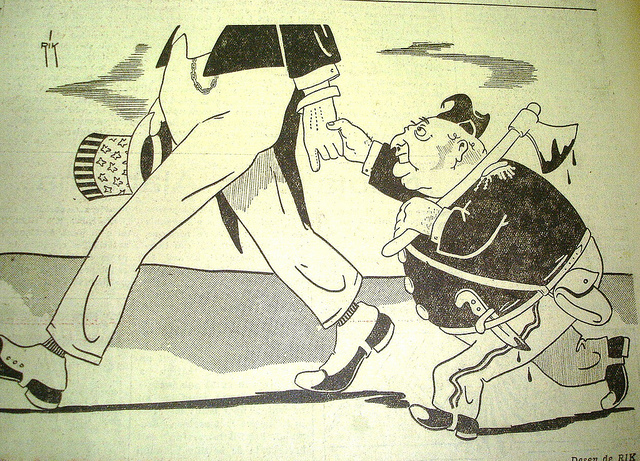

Another important feature is that, already mentioned, of these drawings being stereotypical (intentionally using a few recognisable symbols, characters and topics, although they manage to offer enough room for humour and satire). Murray J. Edelman (qtd. in Ştefan Borbély 2002: 142) implies that constructing the “enemy image” (together with the invention of a complex of social fear and xenophobia) involves a few defining stereotypes of representing the enemy. I shall focus precisely on these stereotypes. The first idea to focus on here is related to the essence of constructing an enemy and the choice of the US to embody this enemy. While in Polish press, as Joanna Witkowska, John Bull and Uncle Sam (symbolic characters which will be mentioned again below) form an alliance in the typology of the enemy, embodiments of the Evil, in Romanian political cartoons the situation is partly different. Although the two symbols appear sometimes together, US is without doubt represented (by the number of appearances, dimensions and other features) as the Number 1 enemy, while John Bull is seldom represented as an equal. Usually the British symbols (John Bull, the British pound, Churchill) are presented as subordinates or dependant to the US power, as it happens to many symbols suggesting other European powers.

Fig. 13.

Fig.14. Title: “The Fight for the markets”

Fig.15. Text: “Uncle Sam: Now that I have them tied together, I have to be careful not to lose them”

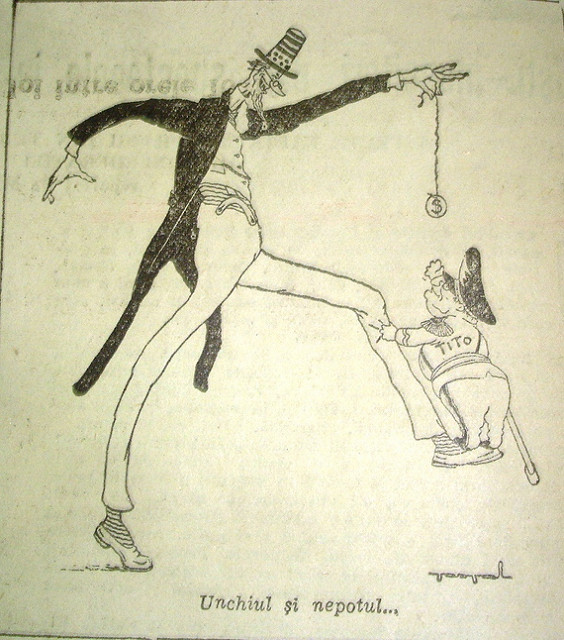

Fig.16. Title: The Uncle and Nephew

Moreover, this relation of subordination is ‘revealed’ as the truth behind the masquerade of independence (the propaganda shows an obsession for ‘revealing’ a hidden truth behind an appearance, the US being represented as an imperialist puppeteer in a political puppet show, a power to which all European states have already been submitted (while the Communist states are still resisting to this evil conqueror). An interesting representation is that of the Vatican as a submitted state, with the Pope depicted as “fed”, corrupted by the American financial force, an image which can be again associated with the religious suggestions present in the image of a devil-like American symbol. This time the religion itself (trough its main representative) is corrupted and can be given no more credit, thus the suggestion is that communism and its beliefs should replace all that symbolised trust before.

Fig. 17. Text: Papă (A wordplay: “papă” meaning both “Pope” and “he eats” in child language).

By cultivating this psychological suggestion that under the friendly appearance of a US ally there is a fierce conqueror, characterised by mystery and dissimulation (having, of course, something evil to hide), the propaganda stimulates the fear which appears in front of the unknown, a feeling of that is intended to be associated with the idea of the dominance of the US. This is achieved by representing in a complex manner (with the use of different symbols and characters) an obvious dissimulation or discrepancy between a positive appearance of the US and a negative reality.

Fig.18. Title: American Nanny

This type of representation can be correlated to Murray J. Edelman’s classification of means of constructing the typology of the imaginary enemy (see Borbély, 2002, 142-143). Among Edelman’s stereotypes on the enemy image, we encounter this mystery, this intentional identity mystification with the purpose to hide a dangerous Truth on the enemy’s intention.

Interesting enough, this stereotypes in constructing the identity of the enemy are used by both sides (Borbély’s study focuses on URSS as perceived by the US propaganda, the stereotypes used by the latter being similar with the ones used by the communist press). Although when quoting Edelman, Borbély speaks of US propaganda, but the analysis of communist representations allows us to draw similar conclusions. A very interesting idea, applicable in both cases, is that the choice and construction of such an imaginary enemy (imaginary because of the artificial or exaggerated features attached to him), a stable, recognisable one (THE Enemy) is comfortable to use for the political regime, maintaining (by all the psychological manipulation) social order and organised reactions at home (a modern, symbolic scapegoat). This may be one of the reasons for which Romanian propaganda in the late19402-early1950s individualise and build such a strong American stereotypical set of representations. Another reason may be that in Romanian collective imaginary, the US is associated with a powerful former ally, symbol of the capitalist world (to which Romanians continue to be attached, as the Communist regime imposed itself without public support), a power that is expected to come and free Romania from Soviet influence. To this Saviour image (see Giradet), the Communist propaganda opposes a very persistent representation as an imperialist power, which only intends to conquer other countries.

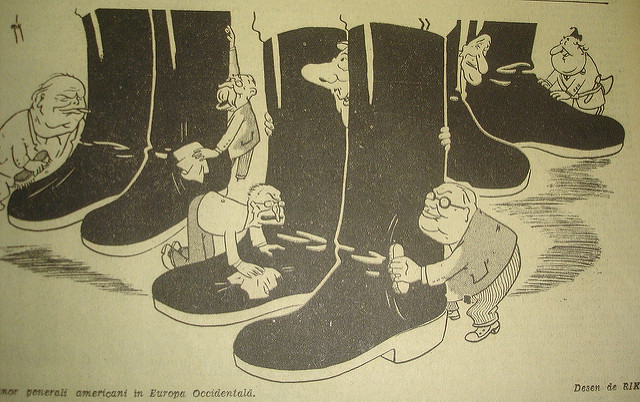

Fig. 19. Text: “General Clay: ‘Let’s see if somebody can say now that we don’t live in a perfect harmony with our Western allies”

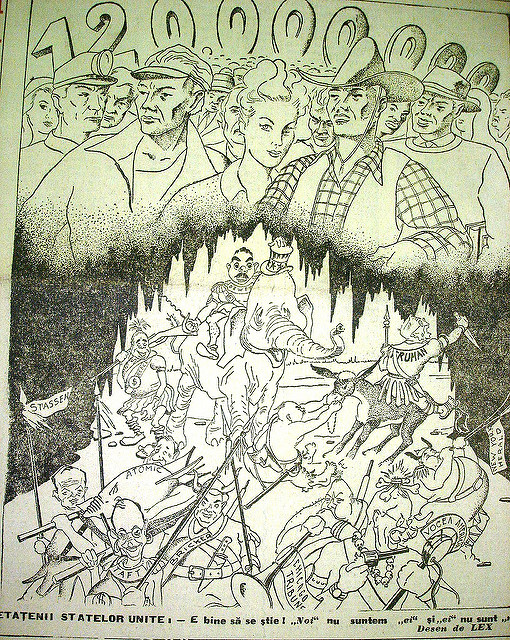

Usually the propaganda refers to the enemy as small and mean in comparison to “us” (the Workers, the proletarians, who are great and numerous or the Soviet power, symbolised by Stalin’s image, always magnificent; besides the dimensions, the communist characters, especially workers, are depicted as serene, most often plain, strong and determined, while the US characters, especially politicians, bandits, businessmen have emphasised negative features and their faces suggest hidden evil intentions, lack of morality, and so on, see fig. 4 and 5). However, when representing the imperialist US, the dimensions when representing the US symbols are always exaggerated when they are placed together with the representations of Western powers (which are considered to be already its political vassals). Thus, THE enemy (US) is represented as superior in dimensions and suggestions to other characters that were sometimes present in the images. Moreover, these Western powers (Italy, France, Germany), which are most often represented (but to which sometimes other countries are added, China, Greece) are shown as humiliated (see fig. 18-19) in relation to the US (suggesting that WE, the Communist countries, are Proud and respectful in comparison to them, as we are not subjects of such humiliation).

Fig. 20.

Thus, propaganda addresses here not to the intellect, but to the psychological level, as the expected reactions are to be emotional (indignation, fear, pity, pride), which are to appear while the receiver (the viewer) is mislead by first level of interpretation, the humorous component of the caricature.

The Obsession of Americanism & Identity Stereotypes

In the articles to which sometimes the cartoons are attached, “US”, “America”, “Americanism” are obsessively present (see fig. 9), many times reduced (both in texts and in images) to the “country of the dollar”, maybe the most recurrent visual symbol attached to this national identity. The titles and texts satirically suggest a decaying world (“America is sad”, “The Symptoms of the Economic Crisis in the US”, “Uncle Sam doesn’t want to study”) or a violent, dangerous power (“American imperialist have designed a ‘murder plan’”). In the newspaper and magazine articles (to which images are most often attached) the name of the enemy (in its different versions: USA, America, American plus a variety of additional terms such as “American culture”, “American art” and so on) is, as showed above, obsessively recurrent.

In the case of images (besides the small text or title) there is a series of visual, significant and recognisable symbols are used, with small variations and sometimes in combination (with the intention to make, by addition, the message stronger), in order to leave no room for ambiguity. A dominant one within such symbols (in the corpus of images analysed here, see below their thematic classification) is the figure of Uncle Sam (usually a very thin figure, with a small beard, wearing a hat with the American flag patterns and old-fashioned and somehow ridiculous clothes, in the Lincoln’s style, see above fig. 12-15).

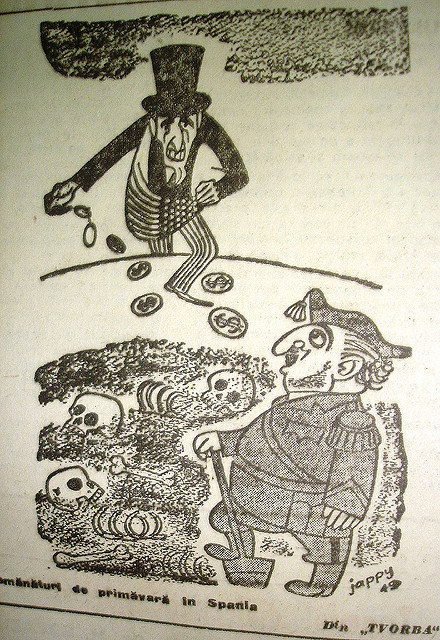

Fig. 21. Title: Spring agriculture in Spain.

The image mixes a series of stereotypical suggestions related to US identity, from caricaturing the bourgeois tradition (by the use of the clothing and small beard) to presenting this symbolic figure very close to a diabolic one (mixing national stereotypes to cultural ones, by copying some of the stereotypical features in the representation of the Devil in the European history of culture) and thus exaggerating the negative features associated with the US image (the absolute evil).

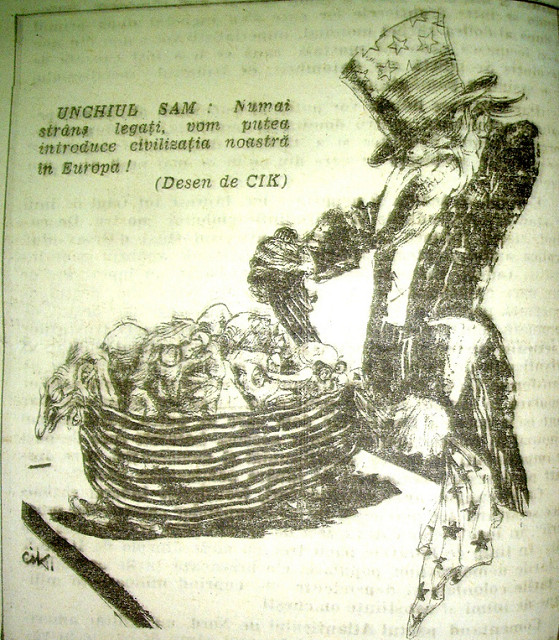

Fig. 22. Text: “Uncle Sam: ‘Only tied together we can introduce our civilisation in Europe’”.

This association addresses the same emotional level, with the intention to induce fear (when the representation is close to a diabolic image or, when for instance the cartoon suggests the economic crisis in the US, which is often represented as a skeleton; other times there appear diabolic images, even dragons, all sorts of frightening images included in order to induce fear) or sometimes despise (when the image is more of a caricature of evil, with only the pretensions of evil power, but actually weak).

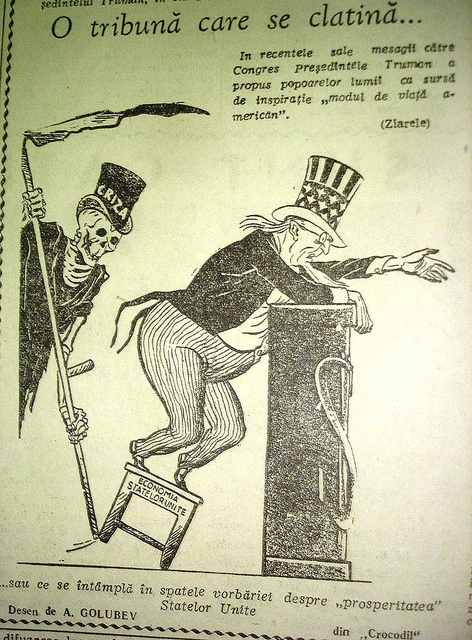

Fig. 23. Title: “A trembling rostrum. Text: …or what happens behind the words about US prosperity”

As we discuss stereotypes in constructing the identity of an imagined, fictional enemy, Edelman’s classification of stereotypes can be mentioned again. One of the propaganda manipulating techniques in connection to this invention of enemy is that of generalising. Often the images present this abstract figure, mentioned before, of the US nation rather than real political figures (see the small number of Truman’s appearances, who himself sometimes is represented very close to the symbolic figure described above). The Americans, the US nation is therefore reduced to some symbolic representations, without letting the enemy individualise himself and therefore allow some emotions to be connected to him (he is not a person but a symbol).

Fig. 24. Text: “US citizens: ‘Everybody should know. ‘We are not them and they are not we’”

A few times “people like us” appear, allowing empathy from the viewer, particularly American workers, large figures similar to the representations of Communist workers, but usually starving, being unemployed and miserable. They are to be pitied but also sometimes suggest they have the potential of changing society, making it similar to ours (the myth of Good winning over the Evil).

Fig. 25. Title: Truman’s Speech. Text: “American workers: ‘If we continue to let these people bless us with their ‘prosperity’, we’ll starve’”

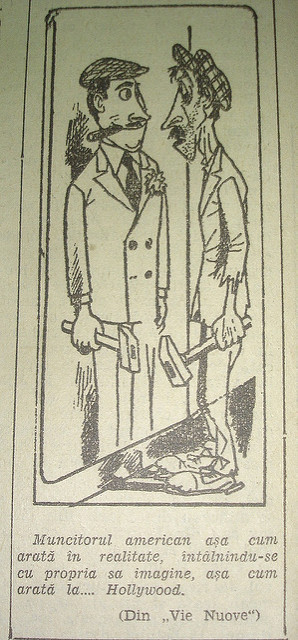

Fig. 26. Text: The American worker as he actually looks like facing his Hollywood image

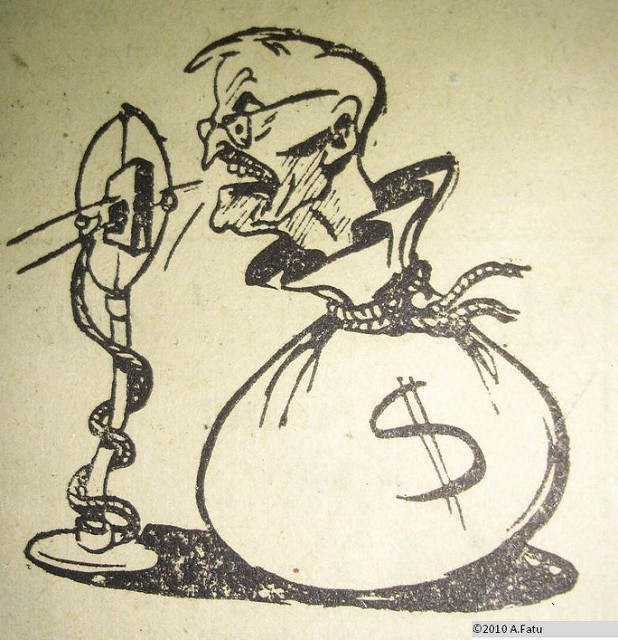

Another very powerful symbol (see its recurrence in the thematic classification below) is the representation of the dollar ($), present in a large number of cartoons, independent or in combination with other US symbols (Wall Street, President Truman, the cowboy, the Statue of Liberty etc.), when the message aims to be more eloquent.

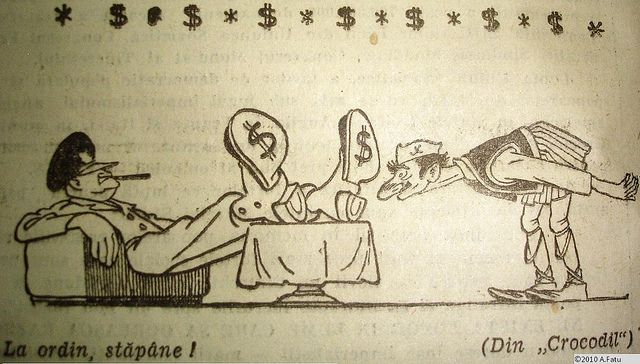

Fig. 27. Text: “At your service, master!”

Fig. 28.

The suggestion behind these representations comes to complete the imperialist suggestions, by presenting the US financial power as the main characteristic of a “dirty” politics, with no morals or ideals (many times Wall Street is depicted as the True power, a puppeteer behind the US president and US politics, press, justice, culture and so on, all subordinates of the Dollar).

Fig. 29. Title: Changing guard at the Department of State

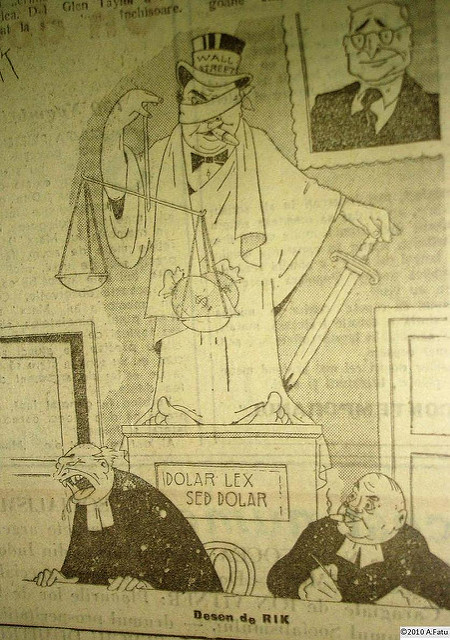

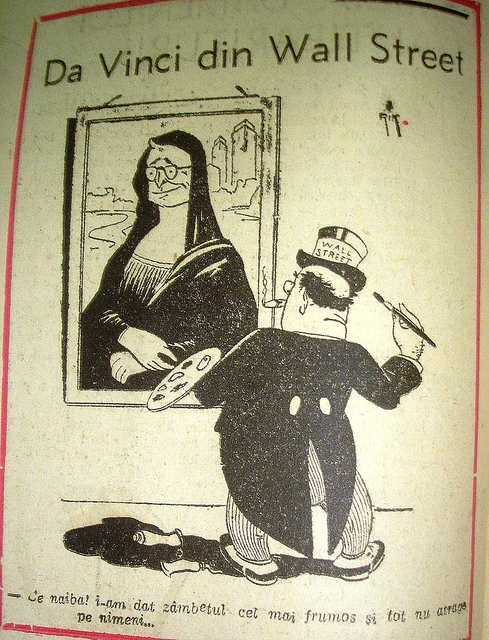

By openly depicting justice (see the text Dollar Lex Sed Dollar, Fig. 30.), politics and culture as being sponsored and therefore influenced by Wall Street business, the cartoons suggest that all levels of the US nation are maculated, distorted by this external influence. Communist politics (with the help of political propaganda, involving ideological distortion of reality) was “fighting” (with its favoured stereotype) with a financial evil rather than with a political one.

Fig. 30.

Justice is corrupted (the “sponsor” makes of course, illegal businesses) and therefore the values promoted by the US state can no longer stand as valid and convincing.

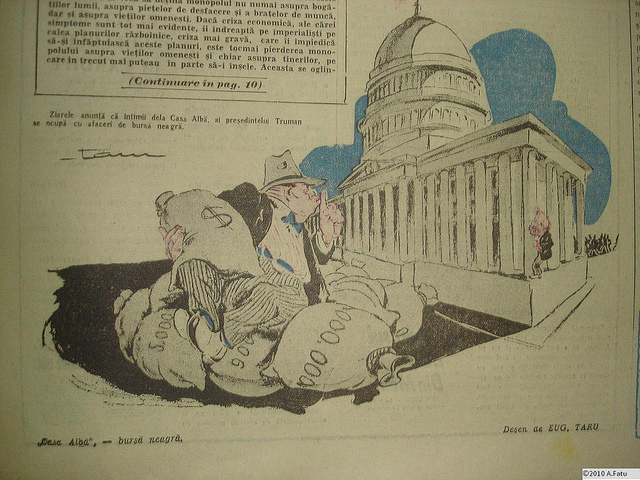

Fig. 31. Title: White House – Black Market. Text: Newspapers announce that people close to President Truman make business on the black market.

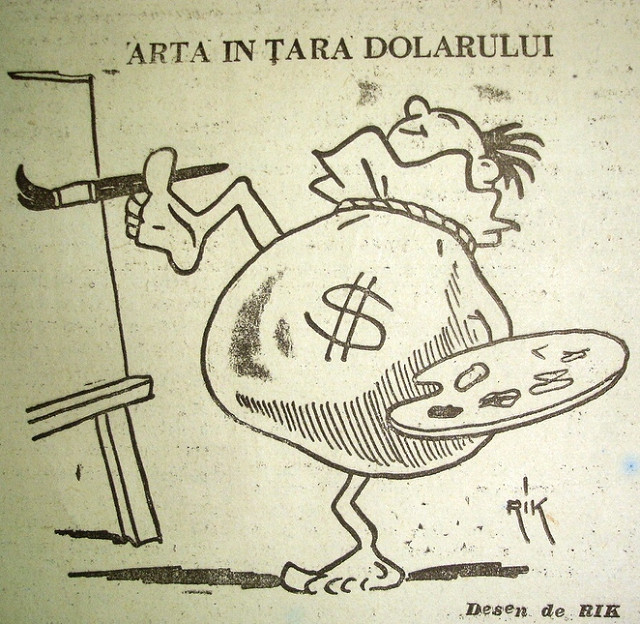

Not only justice, but also press, art, education, politics, press, justice, culture and so on are represented as subordinates of the Dollar. Paradoxically, a propaganda proclaiming ideologically engaged art and a culture (Socialist Realism, planned work, topics from the “real” proletarian life) is criticising in its caricature representations on the US, an impure art (sold to the financial god, one of the cartoons being entitled “Arta în ţara dolarului” [Art in the country of the dollar]) and a decaying culture.

Fig. 32. Title: “Art in the country of the Dollar”

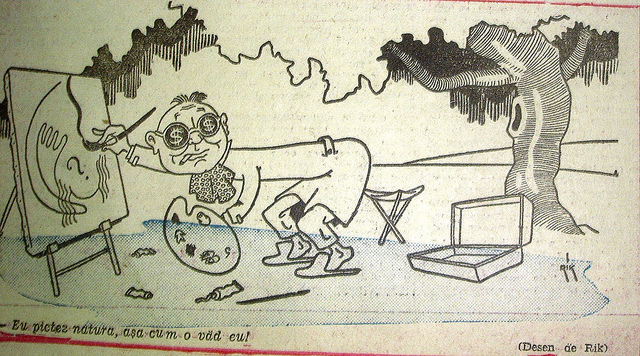

Fig. 33. Text: “I paint nature as I see it”

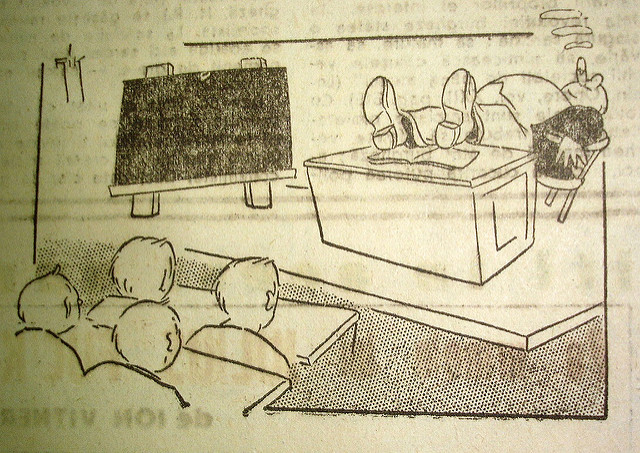

As I mentioned impurity, a larger discussion needs to be open here. The enemy is represented (and this is another stereotype, transgressing regimes and culture if we refer to Edelman’s classification) dirty, somehow inhuman, tribal, without high values (see Borbély, 2002, 142). The representation of this idea in the images analysed (and a reason can be their origin, mostly culture magazines and newspapers) is complex and refers mainly to a decadent, corrupted culture, on the way to disappear completely. This image is achieved by associating visual representations to articles on the subject (see for instance the text “Uncle Sam doesn’t Want to Study”, associated with the representation of a school where nobody works/learns, see fig. 35). The most immoral aspects are associated to culture, from this lack of interest in study and learning (illiteracy is depicted as a real threat; students are represented as lazy or vicious, see Fig. 35.) to education and art produced or corrupted by money (art, philosophy, literature becoming means of expressing a pro-war, political message).

Fig. 34.

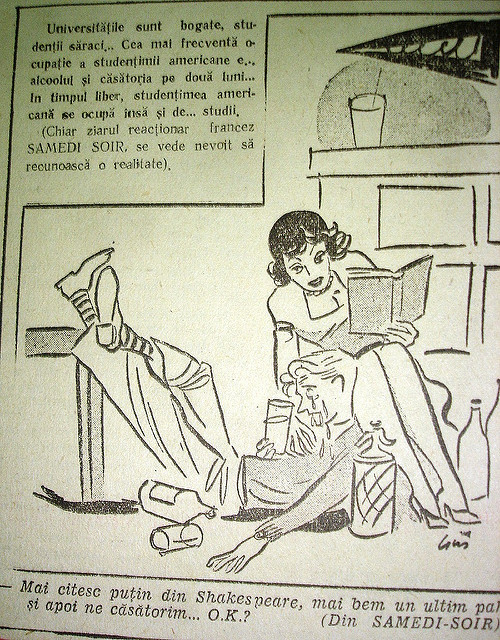

Fig. 35. Comment: “Universities are rich, students are poor. The most common habit of American students is drinking alcohol and getting married for two months. In their spare time, American students also…study”.

Text: “I read a bit more Shakespeare, then we drink a last cup and then we get married, ok?”

This type of Manichean formulas as those used by Communist propaganda try mainly to induce models and anti-models and therefore a culture (not only decadent but actually represented as decaying) is clearly not a model for the “healthy” communist society. By this suggestion of the imminent death of a culture (advertising and commercial art as well as propaganda works replacing a real culture, while the education is disappearing) the cartoons address not to common viewers but especially to intellectuals, in order to make them believe their political message (culture is possible only under the Communist regime, in its terms).

Fig. 36. Title: Wall Street Da Vinci. Text: “‘Damn! I gave it the most beautiful smile and still doesn’t attract anybody’”.

A very interesting aspect is that the propaganda becomes very subtle here, making use of suggestions and symbols coming from the European cultural tradition, not only from the Eastern Europe: Da Vinci, the Tower of Pisa, Rembrandt and so on). The communist propaganda becomes a culture supporter (the Western countries being represented as those forbidding readings and art development, while in reality the Communist, totalitarian, regime was far more restrictive). The American culture is depicted as gradually transforming into a tabloid culture (the actual term “tabloid” is used, although in Romanian press it had no significance at those times), focused on the evil part of life (violence, brutality, scandal), the lack of value being implied as a natural effect (ignoring the principles and features of aesthetic value, which doesn’t lie in the choice of a topic). Realism is proclaimed as the ultimate cultural formula, while modernism, surrealism and so on, are considered caricatures and childish imitations of art (see fig.11). Another suggestion (made both in articles and visual representations) is that the social evil depicted in these American simulacrums of works of art (considered to lack seriousness and morality) actually characterised American society. The climate existing in the US is depicted as characterised by violence and insecurity (also associated with the economic crisis and unemployment). In opposition, the communist society is depicted as serious, mature, moral and focused on work and economic progress (see fig.4).

Fig.37. Title: In the US. Text: ‘Tomorrow we break into the Central Bank. Go and see what’s new in the bookstores on breaking safes”.

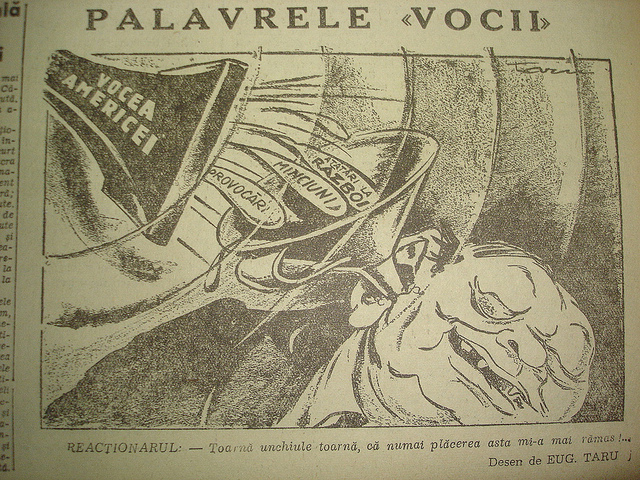

The American society is depicted as a society in crisis (moral, economic and so on, revealing a society on the edge of self-annihilation), contrary to the “American dream”. Again the message addresses to the emotional level, trying to induce the idea of insecurity, almost of fear (bandits). In order to do this, the images use both cultural references and trivial ones (Hollywood movies), a complex of exaggerated, partial or distorted features from which an abstract identity construct is achieved. The idea of social insecurity is induced through a complex of suggestions, an important level being represented by the depiction of social problems – unemployment, economic crisis, hidden beneath a prosperous mystification (see fig. 23, 25). Speaking of the latter (the lie or deceiving being a strong, recurrent theme, as showed above), political cartoons make reference (although just in a few representations) to the “mystification” or “disinformation” of Western propaganda (especially through the radio, Vocea Americii (Voice of America, VOA).

Fig. 38. Title: The twaddle of the “voice”. Text: The reactionary: “Poor, uncle, poor, it is the last pleasure I’ve got”.

When speaking of propaganda encouraging a feeling of insecurity, we have to take into consideration another very important issue, especially for the very delicate context of the late1940s, when the World War II was not very far behind: the threat of another world conflagration (see fig. 1, 6, 7, 9 and others). War versus peace (always connected with the Manichean formula West/US versus Eastern Europe) is an opposition largely represented in the group of political cartoons analysed. This opposition, conceived in a very delicate post-war moment, but also comes in the Marxist tradition of associating capitalism with war and was intended to be a very persuasive and have emotional impact especially on the grounds of a recently ended military conflict (in such situations US is represented as a person in military uniform, bearing some recognisable US symbols: flag, symbol of the dollar or simply the abbreviation US).

Fig. 39

Fig. 40. Title: The Peace Treaty. Text: ‘I can’t sign, I have both my hands engaged in other businesses’

While US is represented as symbolising war, as associated with imperialism and focused on weapon industry, the Communist countries in the Soviet block are represented as focused on “real” economy and always supporting world peace (the dove), although, paradoxically, this defence of peace is sometimes represented also as “fighting”. The ideological “fight” as well as the “fight for peace” are recurrent images, but despite the suggestion of conflict, the representations try to convince of the pacifist specificity of the communist regime so when the images do not depict the dove, another symbols are opposed to the images of war (US weapons or other symbols of war): the communist weapons are, even in these political cartoon, the well-known sickle and hammer, sometimes accompanied by interesting suggestions (such as the pen, symbolising ideological rather than intellectual activities, see fig. 7).

Conclusions

Analysing an important number of political cartoons, images reproduced from Romanian cultural magazines or newspapers (Flacăra (1948-1949), Contemporanul (1949), Almanahul literar (1950), Scânteia (1949), Scânteia tineretului (1950), some patterns became obvious, either in the topics and characters represented or in the means the artists used, following the model of Soviet political cartoons (equivalent to a canon in religious painting). The obsessions of the communist propaganda in relation to the US become obvious also when analysing and comparing the numbers.

|

Issues |

Number of images |

|

1. American Symbols (i.e. Statue of Liberty) |

20 |

|

2. American Workers |

5 |

|

3. Crisis/ unemployment in the US |

17 |

|

4. Dollar |

65 |

|

5. Ideological conflict (left vs. right) |

16 |

|

6. Illiteracy/ culture issues |

13 |

|

7. Imperialism |

80 |

|

8. Marshall Plan |

4 |

|

9. North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

15 |

|

10. Peace/ War |

48 |

|

11. President Truman |

18 |

|

12. Racism |

8 |

|

13. Stealing/ scandal/ violence in the US |

10 |

|

14. The Pope – US agent |

5 |

|

15. US Decadent art and literature |

28 |

|

16. US Justice |

9 |

|

17. US Propaganda |

4 |

|

18. Wall Street |

32 |

Table 1. The issue treated by the analysed political cartoons and number of their appearance.

Fig. 41.

Fig. 42. Title: In the desert of crisis. John Bull and the sack of…pounds. Text: “‘If only I had dollars instead of pounds…’”

If we select only the issues which repeat most frequently (US imperialism, dollar/US as a financial power, the threat of war and Wall Street power, to count only the most representative figures), the result shows clear connections to the Cold War (then at its beginning) and what it meant, also shows which were the most important political worries in the Soviet block at the time (because the Soviet influence is obvious, sometimes the images are copied directly from URSS periodicals, as mentioned before, other times they copy characters and symbols, such as the skeleton of economic crisis or are just “in the manner of…”). Another interpretation (even more creditable in the context of the analysis above, about the intentional and complex construction of a stereotypical enemy) would be that these fears were not the actual ones at the political level, but were the ones official propaganda wanted to induce to the people (a feeling of insecurity and fear of a new war, despise towards a financially corrupted world, within which nothing is pure and creditable anymore, starting with justice, religion, art, education).

Fig. 43. Title: The New York Trial. Text: Judge Medina reads the sentence of the court.

The important role played by political cartoons within propaganda (with a particular reference here to Communist Romanian propaganda from the late 1940s-early1950s) is not a minor one, as the message of such a distorted image penetrates (or at least is meant to) beyond the humorous appearance, addressing to deeper emotions and fears. Due particularly to its innocent humorous appearance, such an image comprises more than a funny message, trying to persuade and manipulate thinking in order to convince it of the regime’s own ideological truths, while all the negative energy is redirected towards an artificial, hybrid identity construct of an “imaginary” enemy. This identity construct is achieved mainly trough the insertion and recurrence of certain identity stereotypes (either imagistic, such as the flag, the Statue of Liberty or more powerful, such as the references to the financial power of the US or to imperialism).

Fig.44. Title: US Liberty and Justice. Text: “Liberty: ‘Oh, my dear, at least you can’t see!”

The obsessive repetition of the same clichés within these images (similarly to the situation of stereotypical language) aims at having even a more perverse effect, making the mind react to them automatically, as to something familiar and natural. Mixing amusement (or hiding behind it) with political serious matters, political cartoons play a unique part among the tools of totalitarian propaganda and in general within the Cold War, because of its hybrid character, of its innocence appearance behind which manipulation was hidden, a game played with the minds (at least in the intention, because often both viewers and artists just pretended – as accepting a convention – to believe the message of propaganda). Moreover, analysing these images as they are (distorted, exaggerated, stereotypical) offer to the current viewer a more complex perception on the political and cultural context, as it becomes obvious that beyond the official discourse (political, ideological, journalistic and cultural) even the aspects considered to be innocent or without importance would not escape “Big Brother’s” careful eye.

Acknowledgement

This paper is supported by the Sectoral Operational Programme Human Resources Development (SOP HRD), financed from the European Social Fund and by the Romanian Government under the project number ID59323.

Works Cited

- Boia, Lucian. Mitologia ştiinţifică a comunismului, Traducere din franceza, editie revizuita si adăugită de autor. Bucureşti: Editura Humanitas, 1999.

- Boia, Lucian. Pentru o istorie a imaginarului, Traducere din franceza de Tatiana Mochi, Bucureşti: Editura Humanitas, 2000.

- Borbély, Ştefan, “McCartysmul”, Caietele Echinox. Restricţii şi cenzură, vol. 4/2003: 35-46.

- Borbély, Ştefan, „Războiul imaginar”, Caietele Echinox. Teoria şi practica imaginii. I. Imaginar social, vol. 3/2002: 138-154.

- Cesereanu, Ruxandra, “Maşinăria falică. Scânteia (1944-1950), Caietele Echinox. Teoria şi practica imaginii. I. Imaginar social, vol. 3/2002: 245-252.

- Coman, Mihai. Introducere in sistemul mass-media, Ed. a III-a revazuta si adaugita. Iaşi: Editura Polirom, 2007.

- Contemporanul. Săptămânal politic-social-cultural, ian.-dec. 1949

- Cuplete si scenete humoristice (Almanah). Bucureşti: 1950.

- Doru Pop, „Abordări empirice în analiza imaginilor”, Caietele Echinox. Teoria şi practica imaginii. I. Imaginar social, vol. 3/2002: 15-30.

- Flacăra. Săptămânal de literatură şi artă (I), nr. 1-52/ 1948; (II), 1-52/1949.

- Girardet, Raoul. Mituri şi mitologii politice. Iaşi: Institutul European, 1997.

- Iacob, Andreea, „Mijloace de manipulare în masă şi cenzura gândirii, Caietele Echinox. Restricţii şi cenzură, vol. 4/2003: 100-108.

- Keeble Richard, (coord.). Presa scrisă: o introducere critică, Traducere de Oana Dan. Iaşi: Editura Polirom, 2009.

- Morar-Vulcu, Călin. Republica îşi făureşte oamenii. Editura Eikon: Cluj-Napoca, 2007.

- Pipes, Richard, Communism: A History of the Intellectual and Political Movement, Phoenix Press: London, 2002.

- Roşca, Luminiţa, Mecanisme ale propagandei în discursul de informare: presa românească în perioada 1985-1995. Iaşi: Editura Polirom, 2006.

- Scânteia. Organ central al Partidului Muncitoresc Român, Seria II, Anul XVIII (1949), ian.-dec.

- Scânteia tineretului. Organ central al tineretului muncitor, Seria II, Anul II (1950), ian.-dec.

- Sweig, Julia E.. Friendly fire: secolul antiamerican – mai puţini prieteni şi mai mulţi duşmani pentru SUA, traducere de Victoria Vuşcan. Bucureşti: Editura Tritonic, 2006.

- Ştefănescu, Simona. Media şi conflictele. Bucureşti: Editura Tritonic, 2004.

- Witkowska, Joanna. "Creating false enemies: John Bull and Uncle Sam as food for anti-Western propaganda in Poland" Journal of Transatlantic Studies 6.2 (2008). 14 Sep. 2010

< http://www.informaworld.com/10.1080/14794010802184309 >

Copyright (c) 2010 Andrada Fătu-Tutoveanu

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.