Michelle Obama is a unique First Lady, and not only because of the color of her skin. Surely, she is the first African-American presidential wife, yet those who believe that her skin color is the main feature distinguishing her from previous First Ladies underestimate her superb personal and professional qualities and ignore her distinctive social background. In the span of just a few years, she has risen from virtual anonymity to world fame. In the meantime, she has also evolved as a role model for many born within and outside of the United States.

Hundreds of magazine and newspaper articles as well as books, the latter also mostly by journalists, have been published since she came to the limelight. They cover a wide range of topics from family life and history through fashion and style to cooking and gardening. Other publications include compilations of her speeches, quotations, and letters, and there are even a number of biographies intended for children. But scholarly interpretations are, understandably, slow to come. The Michelle Obama phenomenon is just too recent history. The present work does not purport to be an exhaustive account. Its primary objective is to draw a historically situated portrait of the First Lady while looking for answers to explain her immense influence and popularity—a significant part of which lies, I argue, in the fact that Michelle Obama is an iconic figure, in many ways, a reflection of American (social) history.

The First Lady is a complex person. She is an African-American woman, a highly skilled professional, a mother, and, overall, a person of influence who has the resources to shape politics and everyday life in the US, and even worldwide. Through her personal and family history, it is also possible to trace the turning points of the nation’s history and the realization of the so-called American dream. The best way to describe the different facets of her identity is to take a multi-layer approach at her: as a representative of American/African-American history; as a representative of black equality; as a representative of women’s emancipation; as a representative of working mothers; and as a manifestation of the American dream. The following pages will address these various aspects of her personality one by one.

A Representative of American/African-American History

The Obamas did not want to make race a central issue during the 2008 presidential campaign. Yet masses of American voters and those following the events worldwide believed that the question of color was indeed a crucial element. Naturally, most attention fell on Barack Obama, not his wife, as many felt that his election to the presidency would symbolize the victory of democracy in a country where the fierce fight against legal racial segregation and discrimination had ended just a few decades before. In the eyes of these people Barack Obama became the incarnation of black equality, his success being a kind of compensation for the sufferings of the African-American community through the ages. But many of these people missed the main point about the president-elect: unlike Michelle’s, his story did not correspond with the stories of the majority of blacks in the United States.

American history is largely about blending various peoples, races, colors, and religions and of trying to cope with the results in social, economic, political, and cultural terms. While the genealogy of Barack Obama offers interesting accounts of mixing cultures, races, and religions—thereby being representative of typical American multiculturalism—there are at least two elements that separate him from the average African-American citizen: his middle-class background and the lack of the slave experience in his ancestry.

In fact, the president might even be identified as a first-generation African-American. His mother, Stanley Ann Dunham, was a white woman originally from Kansas, whose family moved to Hawaii after her graduation from high school. She was studying cultural anthropology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, where she met Barack Hussein Obama, a would-be economist who had come to the US as an exchange student from Kenya. Their only son, now president of the United States, was born soon afterwards in 1961 (Mendell 2008, 33–38).

Both parents completed their studies: the president’s father eventually held an M.A. from Harvard University while his mother obtained a Ph.D. from the University of Hawaii. Although Barack Hussein, Sr. left the family when his son was only two years old, his former wife and her parents managed to maintain a comfortable living and provide an elite education for young Barack. No surprise that after reading the manuscript of his autobiographical Dreams from My Father in the mid-1990s, a potential publisher noted that: “After all, you don’t come from an underprivileged background” (Obama 2004, xvi).

As opposed to her husband, Michelle Obama might rightly be called a true representative of both American and African-American history. “The story of my father is the story of America,” she claimed while touring college campuses in the southern United States in 2007 (Lowen 2009). The ancestors of the First Lady include black Americans, white Europeans, and Native Americans; slaves and free citizens; poor and rich; Christians and Jews—exemplifying the melting pot phenomenon, so characteristic a feature of life in the US. Her family’s slave background and her working-class origins accentuate her connections with the black community itself and make her a more authentic representative of the black experience—at least up to some point in her life… As her husband put it during the presidential race: she is “the most quintessentially American woman,” “a black American who carries within her the blood of slaves and slave owners” (Murray 2008, 3).

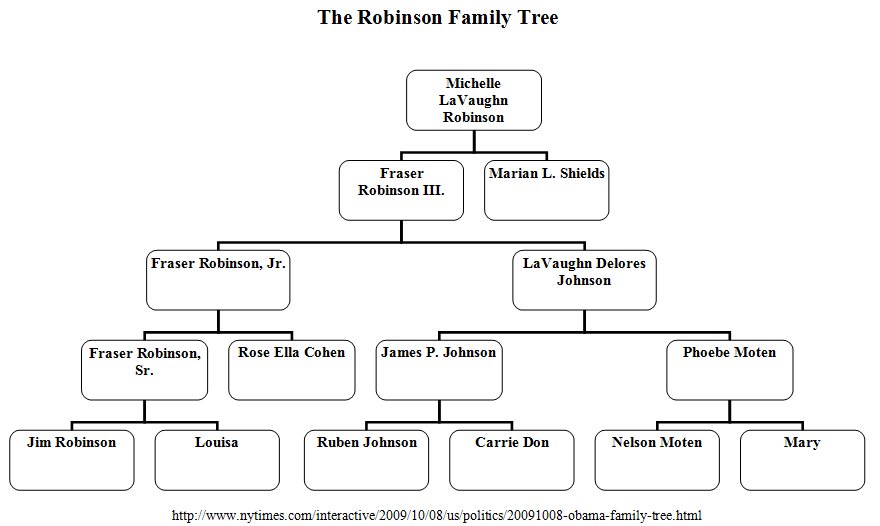

Michelle Obama was born Michelle LaVaughn Robinson in Chicago on January 17, 1964, but her family story takes us back to antebellum South Carolina. Jim Robinson, her great-great-grandfather is the earliest known relative on the Robinson family tree. He was born around 1850 and, like most blacks at the time, he worked as a slave on a thriving plantation, which produced rice in Georgetown. Union victory in the Civil War resulted in emancipation and made Robinson a free man. He nevertheless continued to live at Friendfield where he worked as a sharecropper (Murray 2008, 1).

Born in 1884 Jim’s second son, Fraser Robinson, Sr., would eventually find his way into the working class. He was a smart boy and, after a while, he lived with a white family who treated him as their own. He even taught himself to read and worked diligently as a shoemaker, newspaper salesman, and lumber mill worker (Murray 2008, 2–3). His marriage with Rose Ella Cohen marked the beginning of a new chapter in the history of the Robinsons.

Rose Ella’s ancestry is a telling example of the American melting pot. She was biracial as her birth was most probably the result of a liaison between a slave and a slave owner, a rather common phenomenon in the age of the peculiar institution. Yet there was another twist to the story. Not only that her supposed father named Cohen was a white man, but he was also a descendant of European Jews, who had moved to South Carolina possibly from Portugal in the late 18th century (Colbert 2009, 46–47). Rose Ella passed this mixed racial, religious, and cultural heritage on to her son in 1912 as she gave birth to Fraser Robinson, Jr., the First Lady’s grandfather (Murray 2008, 3). His story too had a lot in common with the experience of a large part of the black population.

With Reconstruction—and Union troops—gone in 1877, southern blacks faced growing unrest and violence, economic difficulties, and Jim Crow segregation at the end of the 19th century. With the coming of the 20th century, the situation only became worse: since the enactment of Louisiana’s infamous grandfather clause in 1898, blacks were losing their legal (especially voting) rights granted to them after emancipation.

To change this state of affairs and in search of a well-paying job, during the Great Depression Fraser Robinson, Jr. decided to leave and move to Chicago, one of the booming cities in the North. He followed in the path of massive waves of African-Americans who, for similar reasons, had chosen to join the Great Migration North. Northward black migration intensified during World War One for two main reasons: because of the growing racial tension in the South and because of the growing need for workers in the North. While, in the past, northern employers had resented hiring African-Americans in great numbers, as the war dragged on decreasing the number of immigrant workers from Europe willing to labor in factories, they began to welcome southern newcomers. Ultimately about 500,000 blacks settled in Chicago alone, most of them on the South Side (Murray 2008, 4; Mundy 2008, 3–4).

Arriving in the early 1930s, Fraser Robinson, Jr. took a postal service job and followed the pattern set in finding a home on the South Side of the city. He married LaVaughn Johnson, a native Chicagoan, in 1934, and the next year their only son, Fraser C. Robinson III, Michelle Obama’s father, was born (Matthiesen). But Fraser Jr., like many of his fellow travelers, grew disillusioned with his new life. Although Chicago opened up new vistas for African-Americans—more and better-paying jobs, a more meaningful sense of freedom, free exercise of political rights—they found that segregation was just as much part of northern life as it had been in the South. Segregated residential areas were simply a fact of life, especially in Chicago, the place that was described even in the 1960s “as one of the most segregated cities in America” (Mundy 2008, 4). The situation worsened during and after World War Two with the onset of the Second Great Migration: the competition for jobs intensified as well as racism, resulting in bloody riots. Fraser Jr. and his wife did not like the changes around them and decided to move back to Georgetown, South Carolina, after retirement (Murray 2008, 2). By this time their son was a grown-up man working for the city’s water plant. In 1960 he married Marian L. Shields, the mother of the First Lady—a woman with mulatto lineage from the South (Swarns and Kantor 2009).

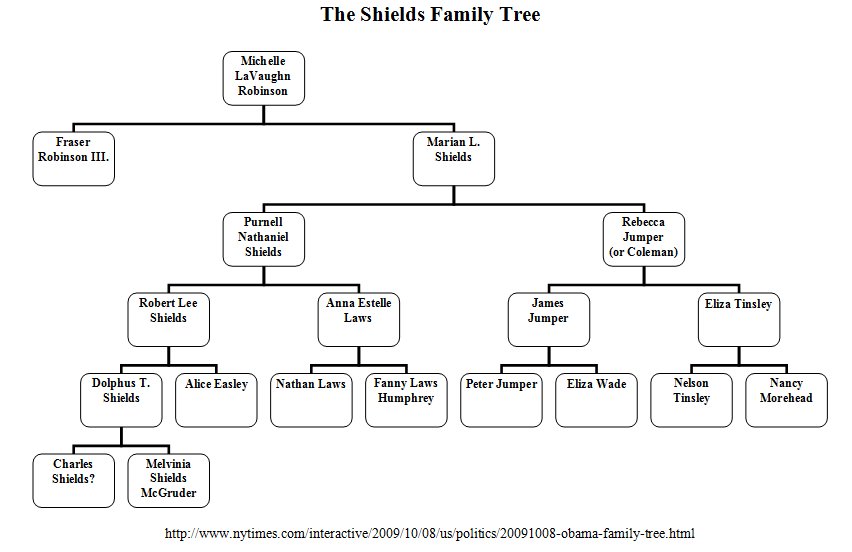

The Shields side of the family is less researched and popularized than the ancestry of the Robinsons despite the fact that the stories unfolding greatly enrich Michelle Obama’s uniquely (African-)American story. According to research performed by professional genealogist Megan Smolenyak, the roots of the First Lady’s maternal lineage go back to colonial times and might even involve Native American heritage. In Smolenyak’s opinion the key family member here is Rebecca Jumper, wife of Purnell N. Shields and grandmother of Michelle Obama, whose ancestors had lived as “free colored persons” even before emancipation. On the basis of findings put forward by Paul Heinegg in his two-volume Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina, she believes that members of the Jumper family were descendents of Tuscarora Indians who, because of their Native American ancestry, obtained their freedom around 1800 (RootsTelevision.com). Free blacks living in the South were a rarity in the pre-Civil War era, adding an interesting feature to Michelle Obama’s family history.

The story of Melvinia McGruder, the progenitor of the Shields family, demonstrates a more common experience of 19th-century female slaves. Just like Rose Ella’s mother in the Robinson lineage, Melvinia was impregnated by a white man, who might have been Charles Shields, one of the sons of her owner. We know for certain that, in 1870, she had four children, three of whom were listed as mulatto on the census record. Among them was Dolphus T. Shields, great-great grandfather of the First Lady (Swarns and Kantor 2009).

Dolphus was very light-skinned, to the extent that he looked almost like a white man. After he had got married, he moved to Birmingham, Alabama, with his wife and set up his own business in carpentry and tool sharpening in a white neighborhood during the first decade of the 20th century. He was a literate man and also an ardent churchgoer, who co-founded First Ebenezer Baptist Church as well as Trinity Baptist Church in Birmingham (Swarns and Kantor 2009).

Michelle Obama’s great-great grandfather lived a long life. He had been born into slavery in 1861 and died in 1950, just as the civil rights movement was speeding up. Not much is known about his son, but we do know that his grandson, Purnell N. Shields, a painter, continued on the northward track and, like so many blacks before him including Fraser Robinson, Jr., he ended up in Chicago. During the Depression years he married Rebecca Jumper, a nurse, and in 1937 they had a daughter named Marian Lois, now “First Grandma” of the United States (Swarns and Kantor 2009; RootsWeb.com).

The two sides of the First Lady’s family became united by the marriage of Fraser and Marian in 1960. The stories of the Robinsons and the Shields had followed the same pattern as they shared a legacy of slavery and mixed racial origin. Also both families had their roots in the South but ended up in the North. The changing social, economic, and political environment made it possible for their descendants in the early 1900s to rise into the ranks of the working class. Yet some of them would aim even higher at black equality after the triumph of the civil rights in the latter half of the 20th century.

A Representative of Black Equality

In 1962 Fraser C. Robinson III and Marian L. Shields had their first child, a boy called Craig. He was followed by a little sister named Michelle, the future First Lady of the United States, two years later. The family rented a one-bedroom apartment on the South Side of Chicago and lived on the single salary of Fraser Robinson, a city water plant employee. His wife stayed home to take care of the children and took a job only when her daughter finished high school. As in the case of most African-Americans at the time, neither parents had a college degree; they lived the life of an urban working class family (Lightfoot 2009, 2–5).

The decades after 1945 saw the political emancipation of black Americans. Although constitutional amendments during the immediate post-Civil War period had granted freedom, citizenship, equal legal standing, and voting rights to former slaves, these mostly remained on the law books. Especially after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, black citizens experienced increasing difficulties in exercising their newly-acquired rights. Almost another century passed before things began to change for the better.

It was the 1950s and 1960s that the civil rights movement really caught on, demanding an end to discrimination and segregation as well as true equality in all walks of life such as education, employment, housing, and political and legal status (especially voting). The 20th-century foundations of the movement were laid by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), still the nation’s foremost civil rights organization, established in 1909. The main objective of the founders was to revive and put into practice the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, thereby providing true equality among colored and white citizens of the United States. The NAACP challenged, first of all, the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision of the Supreme Court, which established the notion of “separate but equal” facilities for blacks and whites and gave rise to Jim Crow segregation practices in employment, education, health care, recreation, transportation, and at all kinds of public places (e.g. parks, restaurants, hotels, theatres, restrooms, and even water fountains). More liberal thinking in the 1930s during the New Deal era and the military necessities and lessons of World War Two—especially the dangers of racial ideology revealed by Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich—hastened improvements in race relations. Yet there was a long way to go before the first effective pieces of civil rights legislation came to be enacted in the 1960s under the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969).

By the time the younger Robinson child, Michelle, was born advocates of black and white equality had made important gains but not enough. President Harry S. Truman (1945-1953) appeared as a supporter of African-American rights and the armed forces were racially integrated as a result. Meanwhile the NAACP continued its arduous job of challenging Jim Crow practices that led to a series of lawsuits. This signaled the beginning of a new chapter in the history of democracy in the United States: a world void of segregated schools, residential areas, and transportation facilities, and a world in which citizens regardless of color could freely practice voting rights.

The civil rights movement intensified in the 1950s and reached its climax just around the time of Michelle Obama’s birth in January 1964. Only a few months later, President Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination in public education, voting, and employment and ended segregation at public facilities. To enforce the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 further strengthened a citizen’s right to cast ballot by outlawing discriminatory measures such as literacy tests that had prevented poorly educated persons, mostly blacks, from exercising their voting rights. Finally, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 sought to end discrimination in public housing. What all these meant for the little black girl growing up on the South Side of Chicago were budding opportunities for better living and education for the moment and opportunities for better employment and social advancement in the future. With new vistas opening up in the 1960s, the surest—and probably the only—way to rise on the social ladder was through education, and Michelle Obama had both the skills and the will to make it happen.

The First Lady was a gifted child indeed. She learned to read by the age of four and skipped second grade at the elementary school she attended. She also joined the school’s gifted class program that made it possible for her to study French early and to take special biology classes at Kennedy-King College. She was not simply smart but also diligent: she was class salutatorian when graduating from middle school (Lightfoot 2009, 5–6).

As a result of the hard work of civil rights activists, Chicago had started an experiment just two years before Michelle Robinson entered high school in 1977. The idea behind the establishment of Whitney M. Young Magnet High School was to erase ethnic boundaries while raising academic standards. Planners projected an equal percentage of black and white students (40 percent each) with the remaining 20 percent being dispersed between the Spanish-speaking community and other races. Although the number of white applicants did not match the original plans, Whitney M. Young became famous for its multicultural nature as well as for its outstanding academic achievements. Just like before, the teenage Michelle proved her excellence: she took advanced placement classes, even college courses at the University of Illinois, and made the honor roll all four years (Mundy 2008, 54–58; Lightfoot 2009, 7).

The foundation of a school like Whitney M. Young was a milestone event in the history of Chicago where, just some fifteen years before, the solution to overcrowded and poorly equipped schools in black neighborhoods had been the setting up of portable classrooms and the introduction of two shifts of classes (Mundy 2008, 51). It demonstrates the remarkable advance city leaders had made in terms of race relations by offering blacks and other minorities the opportunity to prove their equal standing in academics with white students.

With graduation nearing in 1981, Michelle had to decide where she wanted to continue her studies. Her primary choice was Princeton, the college her brother went to. However, despite the fact that she was a smart and studious student, some of her teachers did not believe that her test scores were high enough for a successful Princeton application (Lightfoot 2009, 8). Of course, Michelle thought otherwise; she did apply and got accepted at first trial.

Princeton, founded in 1746, is one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in the United States. Yet, at the time of Michelle Obama’s application, it was also the whitest and most tradition-minded institution of higher education; the “most Southern in spirit … of the Ivies” according to the The Official Preppy Handbook in 1980. African-Americans were denied admission for a long time. Although there had been a few blacks over the centuries who gained the privilege to study at Princeton, many of them did not earn a degree and African-Americans began to appear on campus in any significant number only in the 1960s. In fact, in 1981, when Michelle Obama started her freshman year, blacks accounted for 8.2 percent (94 persons) of the total number of admissions (1,141 persons) (Lightfoot 2009, 14–15).

The elitist university leadership (and tradition) had not allowed women to enter the gates of their institution either, who had to wait until 1969 to gain admission to Princeton. Therefore, being an African-American female student, the sight of Michelle on campus was still a rarity in the early 1980s. She found the existing racial boundaries difficult to cross and even harder to demolish. The separation of blacks and whites among the student body—in terms of residential halls, social clubs, friendships, etc.—was hard-felt. She was aware of the existence of color differences so much as to write her thesis on “Princeton-Educated Blacks and the Black Community.” The question that puzzled her most was “if, in the eyes of her white classmates, she would ‘always be Black first and a student second’” (Lightfoot 2009, 14–22). Yet the future First Lady did not back down: after earning her B.A. in sociology and African-American studies, she decided to apply to Harvard Law School—yet another old, prestigious, and world-famous institution of the United States—and got admitted (WhiteHouse.gov).

At Harvard she experienced some of the same racial problems as at Princeton but, again, she stayed focused on studying and also on charity work. Yet an important change in her personality occurred during her law school years. As her advisor, Charles Ogletree, put it, she grew so confident as to realize that “she could be both brilliant and black” (Lightfoot 2009, 29–32). It might have been this growth in confidence that pushed her towards participation in demonstrations demanding an increase in the number of minority students and professors on campus. She also turned to recruiting African-American undergraduates to Harvard Law from other schools (Wolffe 2008, 1). In the process, she had become not just a representative but an open advocate of the cause of black equality.

A Representative of Women’s Emancipation

By simply being a graduate of Princeton and Harvard, Michelle Obama had made an important step towards becoming also illustrative of women’s emancipation. Yet she did not stop there. After leaving law school in 1988, she began working for Sidley & Austin, a prestigious law firm in Chicago. As one of just a handful of African-American lawyers there, again, she counted a rarity. But, despite her color and sex, she quickly became a well-respected associate soon expected to get promoted to partnership. She did not need outside help on the way up. Although, it happened during this time in 1989 that she met her future husband, her professional rise was her own achievement. In fact, at the beginning of their relationship, Barack Obama was still a law student working as a summer associate under Michelle’s tutelage (WhiteHouse.gov; Lightfoot 2009, 33–34).

As in the case of black civil rights, the accomplishments of the other major social movement in post-war America, i.e. the fight for women’s liberation, were essential in paving the way for the emergence of a successful Michelle Obama. Of course, we must not underestimate her abilities and determination, without which she could have gone nowhere. But it is clear that without significant progress in the field of women’s rights, she could not have reached as high as she ultimately did.

As a result of the feminist revival, just about the time Michelle Obama was born, significant political changes affecting women were taking place. Already in 1961, John F. Kennedy (1961-1963) set up the President’s Commission on the Status of Women to explore the matter more deeply. Its report two years later revealed “substantial discrimination against women in the workplace” and subsequently suggested the introduction of “fair hiring practices, paid maternity leave, and affordable child care” (Imbornoni 2000-2007b). Congress consequently passed the Equal Pay Act of 1963, which outlawed lower payments to women than men for the same job. Kennedy’s assassination prevented him from seeing the practical application of the new law but his successor, President Johnson, continued the work he had undertaken. Although mostly remembered as the crowning achievement of the movement for black equality, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 entailed some important gains also for women: the equal opportunity provisions of the act banned sex discrimination in employment in general (Imbornoni 2000-2007a; Ourdocuments.gov).

Another initiative of the Kennedy administration that was put into practice under Johnson was the introduction of affirmative action programs to ensure racially unbiased employment. Although the original idea had not included women, the program was extended in 1967 in order to provide protection for them as well and not only in employment but also in the field of education. Equal educational opportunities remained the focus of attention in the early 1970s, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 banned sex discrimination in schools. As a further improvement in the status of women, a 1973 Supreme Court decision made it possible for them to apply for better paying jobs previously open only to men (Brunner; U. S. Department of Labor; Imbornoni 2000-2007a).

From the viewpoint of Michelle Robinson’s story, the increasing educational and professional opportunities opening up for women in the 1960s and 1970s were crucial. These were the decades of her childhood and youth, and the changes that came about during those years made it possible for her in the 1980s to attend the schools she wanted and to get the job she wanted.

At the time Michelle Robinson went to Princeton and Harvard, female students at both institutions were relative newcomers. Undergraduate coeducation at Princeton had been barely more than a decade in practice when she started her freshman year in 1981. The Board of Trustees had authorized an investigation of the possibility of admitting women to undergraduate programs in 1967, resulting in a 16-month study, which ultimately embraced the idea. 1969 was thus the first year women could apply to Princeton. Although it all started with separate admission quotas for male and female applicants, 171 women gained admission along with 819 men. This discriminative practice survived for five more years, and women gained equal access to a Princeton education only in 1974 (Leitch 1978a, 1978b).

Of the two institutions of higher education Michelle Obama attended, Harvard Law School had been more responsive to the demands of change. Although law was considered a male profession in the 1940s, and for decades even after, as early as 1949, Harvard Law set up a Committee on the Admission of Women to explore the possibility of opening up the school to able female candidates. Women were accepted by all but two graduate-level departments of the university at the time of the Committee’s report: the Business School and the Law School. The Committee found that the justifications “for the continued exclusion of women … [were] insufficient” and recommended “that beginning in the Fall of 1950 qualified women applicants be admitted to the Law School.” The subsequent faculty vote was 22 to 2 in favor of female admissions (Hope 2003, 265–71). Yet the number of applicants remained low.

These days women make up about half of the student body and one-fourth of the faculty at Harvard Law. But in 1964, the year Michelle Obama was born, only fifteen women (2.9 percent) graduated in a class of 513, and female lawyers like present-day Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg—graduating in the 1950s—had difficulties finding a firm to hire them just because of their sex. Still, in the 1980s, when the would-be First Lady attended law school, there were only five female faculty members between 1984-1993—such an unusual circumstance that the school administration did not bother installing a ladies’ toilet at the faculty library despite having two restrooms there (Hope 2003, xix, 263–64).

Thanks to the work undertaken by women’s rights advocates and also to her own qualities, Michelle Robinson got hired by Sidley & Austin right after graduation. But despite her successes and rising career in corporate law, she could not find satisfaction in her job, which mostly concerned transactional and anti-trust issues (Lightfoot 2009, 33–34). According to Quincy White, her former boss at the firm, he “couldn’t give her something that would meet her sense of ambition to change the world” (Mundy 2008, 103). She finally decided in 1991 that she wanted to work in an area where she could do more for the community and subsequently left her well-paying position for more personally rewarding work in the public sector. Her colleagues at Sidley & Austin contented that “She would have been a superstar” in case she stayed but Michelle would not change her mind. She took a job to work for Mayor Richard M. Daley at Chicago’s City Hall (Lightfoot 2009, 36–37).

Michelle experienced continuing professional success in her new positions as she moved from one job to the other over the years: from City Hall to Public Allies Chicago, from the University of Chicago to the University of Chicago Medical Center. Yet, a truly emancipated woman as she is, Michelle Obama did not resist the more traditional female roles. Following her wedding in 1992, she embarked on a new adventure as she gave birth to her first child, Malia, in 1998 and to her younger daughter, Natasha nicknamed Sasha, in 2001 (Lightfoot 2009, 40–41). Now it was time to prove herself in a hitherto unexplored area: motherhood.

A Representative of Working Mothers

The transition from being a couple to being parents is never easy. It was not easy at the Obama household either. At the time her daughters were born, Michelle Obama was working as Associate Dean of Student Services at the University of Chicago and as Director of the University Community Service Center. Besides her demanding roles as a professional and as a mother, she had to deal with the consequences of her husband’s growing responsibilities that resulted in his frequent absences. Barack Obama had just embarked on a new adventure of his own as he entered the world of politics in 1997 as a first-time state senator of Illinois. While still serving on the state legislature, he also ran for the US House of Representatives, and subsequently lost, in 2000 (Lightfoot 2009, 41; Mundy 2008, 145, 150–53). His new career in politics meant that the heft of the burden of caring for their children and home fell on his wife. While trying to balance work, family, and household duties, she faced the same basic problems everyday women do.

Not surprisingly, one of the main issues on Michelle Obama’s agenda as a First Lady concerns the challenges of working mothers. The fact that she is one of them makes her a credible authority on the subject. As opposed to most previous presidential wives, with the obvious exception of Hillary Clinton, she had built a successful—and extremely demanding—career on her own before moving in the White House. It was not only the type of work she was doing that demanded a large part of her energies and attention but she herself expected much from herself as well as from her colleagues. Her former bosses and coworkers, including Vanessa Kirsch, who hired her to lead the Chicago office of Public Allies, a nonprofit organization that urged young people to take jobs in the public sector, have described her as extremely hard-working. According to Kirsch “There were days when, even though she worked for me, I definitely felt like I worked for her” (Mundy 2008, 131–32).

With such high standards of work ethic, it was difficult to adjust to her new role as a mother. Like millions of working women all around the world, Michelle Obama was constantly feeling guilty about not spending as much time with her daughters as she could have if she had been a stay-at-home mother (Lightfoot 2009, 45). All this coupled with the almost continuous absence of her husband made her feel like a single mother. After Malia was born, Barack Obama was away legislating in Springfield three days a week and even when he was at home he was preoccupied with his other professional obligations including teaching and legal work. Things got worse during his unsuccessful campaign for Congress and, by the time their second child was born, his wife would tell him that she “never thought [she’d] have to raise a family alone” (Mundy 2008, 148–51, 186–87).

With all the work and responsibilities of caring for two young children laying on her shoulders, Michelle Obama came to the point of thinking about quitting her job and becoming a full-time mother after she gave birth to Sasha. But, in the end, she decided otherwise. She figured that if she implemented some changes, she could make life more livable for herself. Good time management is a must for working mothers, and she did a great job in this regard. For one thing, she started going to the gym at 4:30 in the morning partly in order to make her husband deal with the girls and the household during her time away. She also realized that she badly needed some outside help to look after the children as well as their home, so she hired a housekeeper and asked her mother to help with babysitting (Mundy 2008, 157–58).

Another challenge of motherhood is finding the means to a well-functioning family. If you have a job, the problem gets even more complicated. Unless, like Michelle Obama, you have the resources to get help from outside the family, much of your time gets devoted to cooking, cleaning, doing the laundry, bathing and feeding children. This leaves little quality time with them, which would be the best way to develop meaningful relationships between kids and parents. With their father being away most of the time, especially after his inauguration as US senator in 2005, the Obama girls needed some extra help in maintaining that kind of close relationship. Their mother first started writing a journal to keep their father updated on family affairs and then later, during the presidential campaign, she bought webcams for her husband and the girls to help them stay in touch on an everyday basis. And, even during this time, she expected her husband to stay involved in their daughters’ lives and to spend as much quality time with the family as possible, joining them on weekends and for special events like parent-teacher conferences, ballet recitals, and birthdays (Mundy 2008, 183; Lightfoot 2009, 68–69).

Although their income was certainly above average, just like other mothers, the future First Lady had to pay attention to financial matters at the same time she was struggling with work responsibilities, varying schedules of family members, childhood diseases, and household chores. Being the more finance-oriented person in the family, she had always been concerned about the money issue. Not only that they had both accumulated large sums of debt from student loans, her husband’s political campaigns also drew heavily on the family’s bank account. The fact that they had both left corporate America for the public sector did not ease the situation either. Until she was hired by the University of Chicago, Michelle Obama had got a pay-cut every time she changed careers. Her starting salary at Sidley & Austin was $65,000 in 1988, which sum decreased to $60,000 a year when she started to work as assistant to Mayor Daley. Another pay-cut followed as she moved to Public Allies Chicago in 1993, with her income skyrocketing three years later as she started her rise at the University of Chicago. It was in 2005 that the Obamas’ financial problems were finally solved. By this time, Barack’s name had become nationally known as a result of his famous speech at the Democratic convention and his successful bid for the US Senate in 2004. Thanks to the royalties from the reprint of his Dreams from My Father and a nearly $2 million advance for his future books, coupled with Michelle’s promotion to vice president for community and external affairs at the University of Chicago Hospitals and a subsequent pay-raise to over $300,000 a year, they no longer had to worry about student loans and future savings (Mundy 2008, 100, 128, 130, 169, 178–79, 192).

The next crucial step influencing the Obama family was Barack’s decision to run for the presidency. Throughout the campaign Michelle Obama had rejected enquires about her planned agenda as a potential First Lady but she repeatedly stated that her “first job” was being a good mother to her children and that she was “going to continue to be ‘Mom-in-chief,’ making sure … that they know they will continue to be the center of our universe” (Lightfoot 2009, 44, 72). Yet it became quite obvious that one of the causes she would promote after inauguration day was the special concerns of working families and, especially, working mothers. On one occasion she addressed the issue in February 2008, she candidly talked about her own struggles: “as a woman, I’ve been told, ‘You can have it all, and you should be able to manage it all.’ And I’ve been losing my mind trying to live up to that. And it’s impossible. It’s impossible. We’re putting women and families in a no-win situation” (Lightfoot 2009, 45). Her influence was reflected by her husband’s proposals on the matter, which included flexible work schedules, more paid sick days, and an expansion of the Family and Medical Leave Act (Lightfoot 2009, 45–46).

So far, as First Lady of the United States, Michelle Obama has proven to be true to her promises and ideals. Her first task after inauguration was to help her daughters in their transition to new life in Washington and the White House. In the meantime, she continued to support the causes near her heart, visiting homeless shelters and soup kitchens, advocating public service, supporting military families, and helping working women balance career and family. She has also become involved in the less traditional roles of presidential wives as she made an unprecedented tour of the federal agencies, expressing her support for important legislation such as the Pay equity law and the economic stimulus bill (WhiteHouse.gov; Romano 2009; Swarns 2009).

Being a conscious mother and an advocate of healthy eating, she had planted a vegetable garden and installed bee hives on the South lawn of the White House—an introduction to her chief policy concern as First Lady. Her Let’s Move campaign was launched in February 2010 as a nationwide program to fight childhood obesity and nurture a healthier generation. Major accomplishments so far include the enactment of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act and the Affordable Care Act; the development of cooperation with schools, food service providers, and chefs to promote healthy eating at educational facilities; teaming up with businesses like Walmart to make healthy foods more affordable; cooperation with sports organizations such as the National Football League, the National Hockey League, and Major League Baseball to encourage children, families, and communities to increase their daily physical activity; and, lastly, cooperation with the American Academy of Pediatrics to have doctors screen for childhood obesity during Well Child Visits (Black 2009; Letsmove.gov).

While performing official duties including trips abroad, for Michelle Obama, her time as First Lady is also a time of relaxation from professional duties. In a sense, she can now be a sort of stay-at-home mom she had longed to be. Yet she continues to be active in areas important to her—areas that reflect her previous career choices in public service.

A Manifestation of the American Dream

Michelle Obama had not been much known outside her native Chicago before her husband’s bid for the presidency. Yet, in just a few years, she has become one of the most popular and influential women in the United States as well as worldwide. Her life has undergone an enormous transformation: the little black girl from the working class neighborhood of Chicago has risen to be a—not just nationally but—internationally known and renowned woman. Essence magazine listed her already in 2006 as among Twenty-five of the World’s Most Inspiring Women and 02138, a Harvard magazine about university alumni, rated her fifty-eighth among Harvard’s most influential former students in 2007. She was also among Vanity Fair’s World’s Best Dressed People in both 2007 and in 2008, and just recently, in the fall of 2010, Forbes Magazine rated her number one among The World’s 100 Most Powerful Women. Whereas she had been number forty one year before, this time she was ahead of such names as Irene Rosenfeld, chief executive of Kraft Foods, media personality Oprah Winfrey, German Chancellor Angela Merker—who had led the list for the previous four years—, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (Lightfoot 2009, 85; Forbes.com).

One recurring theme of American history is the story of the self-made man. In the person of Michelle Obama we can detect the story of the self-made woman who, despite great odds, such as her working-class background, color, and sex, managed to reach as high as to become First Lady of the United States. On the way to the top, she has experienced much hardship and overcome many roadblocks but her basic personality traits have remained untouched. A large part of her popularity, influence, power, and inspirational nature lies in the very fact that she has remained a real life person in the meantime, not taken away by success. She places heavy emphasis on her role as a mother, which comes on top of her role as a professional. She emphasizes the importance of having a good family life and traditional family values. She, just like her husband, likes to remind people that they are one of them: they have to “pay taxes and pay for [their] kids and save for retirement” (Mundy 2008, 192). Many voters do feel connected with the First Lady when they say that “Michelle Obama seems like a neighbor—just a working mom juggling many of the same issues that plague every household.” Many have the same view of the First Couple: “They remind me of just a regular couple who won the lottery” (Romano 2009, 2).

In the end, Michelle Obama emerges as a role model who, at the same time, epitomizes the American dream—the dream that everything and anything is possible if one tries hard enough. As the historian James Truslow Adams put it in his 1931 The Epic of America, this dream of the American people had grown out of the hope that a better life was possible for every single US citizen regardless of class origins (Adams, n. d., 378–79). Yet, for a long time in the country’s history, the dream was not available to all. The aspiring First Lady herself made testimony of this fact during the presidential campaign in 2008 as she remarked:

…the truth is, I’m not supposed to be here, standing here. I’m a statistical oddity. Black girl, brought up on the South Side of Chicago. Was I supposed to go to Princeton? No … They said maybe Harvard Law was too much for me to reach for. But I went, I did fine. And I’m certainly not supposed to be standing here (Wolffe 2008, 8).

Still, with some exaggeration, it is the rags-to-riches version of the American dream what we can see realize through the life story of the First Lady. She started out as the second child of African-American parents who never had the opportunity to attend college. They lived in a tiny apartment on the South Side of Chicago, a typical working-class and predominantly black neighborhood. Despite her humble beginnings—at least as far as finances are concerned—young Michelle later attended the best schools in the country and built a successful career. Surely, she also got lucky for a number of reasons. She was fortunate to have been born into a loving, supporting but intellectually demanding family where she also had the opportunity to experience and learn to fight physical and financial hardship. She learned about discipline, endurance, and the importance of stern principles in life. She was also lucky as she was born and brought up at an age when the black civil rights and the women’s movements climaxed, giving the chance for a young girl with her skills and determination to soar. She was also fortunate to have married a man with similar qualities and the inclination to let his wife follow her dreams. Yet luck alone does not explain her unique success. It is also Michelle Obama’s talent, iron will, and personal character that allowed her to realize the American dream.

Conclusion

What we have seen through the pages of this essay is the unfolding of an immensely successful personal story. But the present First Lady is not simply successful, she is also popular—two features that do not necessarily go hand in hand. The reasons for her popularity are various including the fact that it is her husband, not her, who makes the big (and divisive) decisions affecting the country. Another explanation lies in her personality: her open and friendly manner that enables her to connect with people easily and her appearance as an ordinary working mom who stands with both feet on the ground. Yet the most crucial element of her popularity is her ability to bring otherwise different groups together in one camp, with no regard to color, sex, or social standing. She can do so because her story resonates with the experiences and wishes of large segments of American society, her amazing life being an example and inspiration to many. This way Michelle Obama has become a role model and even more than that: a real-life person turned icon of American history.

Works Cited

- Adams, James Truslow. n. d. Amerika eposza: Az Egyesült Államok története [The Epic of America: The History of the United States]. Translated by György Pálóczi Horváth. Budapest: Athenaeum.

- Black, Jane. 2009. “Shovel-Ready Project: A White House Garden.” The Washington Post, March 20. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/19/ AR2009031902886.html AR2009031902886.html.

- Brunner, Borgna. 2000-2007. “Affirmative Action Timeline.” Pearson Education, publishing as Infoplease. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://www.infoplease.com/spot/affirmativetimeline1.html.

- Colbert, David. 2009. Michelle Obama: An American Story. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Forbes.com. Accessed November 6, 2010. http://www.forbes.com/profile/michelle-obama.

- Heinegg, Paul. 2011. Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina from the Colonial Period to About 1820. Clearfield Co. Accessed January 23. http://www.freeafricanamericans.com/Virginia_NC.htm.

- Hope, Judith Richards. 2003. Pinstripes & Pearls: The Women of the Harvard Law Class of ’64 Who Forged an Old Girl Network and Paved the Way for Future Generations. New York: Scribner. Accessed January 23, 2011. http://www.amazon.com/gp/reader/074321482X#reader-link.

- Imbornoni, Ann-Marie. 2000-2007a. “Women’s Rights Movement in the U.S.: Timeline of Events (1921-1979).” Pearson Education, publishing as Infoplease. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://www.infoplease.com/spot/womenstimeline2.html.

- ———. 2000-2007b. “Women’s Rights Movement in the U.S.: Timeline of Events (1980-Present).” Pearson Education, publishing as Infoplease. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://www.infoplease.com/spot/womenstimeline3.html#ixzz14j1XQxIq.

- Leitch, Alexander. 1978a. A Princeton Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Accessed January 12, 2011. http://etcweb.princeton.edu/CampusWWW/Companion/women.html.

- ———. 1978b. A Princeton Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Accessed January 12, 2011. http://etcweb.princeton.edu/CampusWWW/Companion/admission.html.

- Letsmove.gov. Accessed February 25, 2011. http://www.letsmove.gov/accomplishments.php

- Lightfoot, Elizabeth. 2009. Michelle Obama: First Lady of Hope. Guilford, Conn.: The Lyons Press.

- Lowen, Linda. 2009. “Michelle Obama – From Working Class Girl to First Lady: Childhood Experiences and Family Struggles Influence Who She Is Today.” About.com Guide, February 17. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://womensissues.about.com/od/michelleobama/a/MichelleWorking.htm

- Matthiesen, Diana Gale. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://dgmweb.net/FGS/R/RobinsonFraserC-LaVaughnDJohnson.html

- Mendell, David. 2008. Obama: Az ígérettől a hatalomig [Obama: From Promise to Power]. Translated by István Bujdosó. Pécs: Alexandra Kiadó.

- Mundy, Liza. 2008. Michelle: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Murray, Shailagh. 2008. “A Family Tree Rooted in American Soil: Michelle Obama Learns About Her Slave Ancestors, Herself, and Her Country.” The Washington Post, October 2. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/10/01/AR2008100103169.html?sid=ST2008100103245&s_pos==

- Obama, Barack. 2004. Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance. Revised edition. New York: Three Rivers Press. Accessed September 12, 2011. http://www.randomhouse.com/book/123909/dreams-from-my-father-by-barack-obama

- Ourdocuments.gov. Accessed January 8, 2011. http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=97&page=transcript

- Romano, Lois. 2009. “Michelle’s Image: From Off-Putting To Spot-On.” The Washington Post, March 31. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/30/AR2009033003332.html?sid=ST2009033103841

- RootsTelevision.com. Accessed January 12, 2011. http://rootstelevision.com/players/player_africanroots3.php?bctid=35742160001&bclid=4865138001

- RootsWeb.com. Accessed January 12, 2011. http://wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=dowfam3&id=I197314

- Swarns, Rachel L. 2009. “’Mom In Chief’ Touches on Policy; Tongues Wag.” The New York Times, February 7. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/08/us/politics/08michelle.html?_r=1

- Swarns, Rachel L., and Jodi Kantor. 2009. “In First Lady’s Roots, a Complex Path From Slavery.” The New York Times, October 7. Accessed October 3, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/08/us/politics/08genealogy.html?_r=1

- U. S. Department of Labor. Accessed January 8, 2011. http://www.dol.gov/oasam/regs/statutes/titleix.htm

- WhiteHouse.gov. Accessed January 12, 2011. http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/first-lady-michelle-obama

- Wolffe, Richard. 2008. “Barack’s Rock: She’s the One Who Keeps Him Real, the One Who Makes Sure Running for Leader of the Free World Doesn’t Go to His Head. Michelle’s Story.” Newsweek, February 16. Accessed January 12, 2011. http://www.newsweek.com/2008/02/16/barack-s-rock.html

Copyright (c) 2011 Dorottya Sziszkoszné Halász

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.